Part Two

Interlude

In Chapter One the main idea was that philosophy — as a method for thinking, as a conversation that unfolds in books, and above all as a way of life — is something that might lift you out of Normal World and leave you stranded in an Unknown City. In one way you’re here to “search for truth,” but in another way you’re here to just . . . wander around, without any particular goal or destination in mind. (But maybe wandering around is actually the only way to search for truth?)

In Chapter Two the main idea was that philosophy — especially as a method for thinking — is something that helps you come up with better answers (not Correct Answers) to the big question about “what you should do” in particular situations. Philosophers use thought experiments like the Trolley Problem to think about their thinking, to reflect on their reactions to situations (the Basic Move). You can think of your reactions as your Normal World. Reflection can take you out of Normal World by showing that your reactions are wrong, or just that you can’t explain why they’re right. And the point of doing this is kind of philosophical work is that if we are constantly reacting to situations in the wrong way, we’re going to be less happy than we could be. The point is to get better at “doing the right thing,” because doing the right thing is what makes us happy.

In Chapter Three the main idea was that if you keep going, if you keep repeating the Basic Move, if you repeat the reflection, then you eventually have to ask yourself whether “doing the right thing” is really going to make you happy — or if doing the wrong thing and getting away with it might actually make you happier. In a way, Chapter Two was still back in Normal World, and it’s only now that you’re really getting transported into the Unknown City. In Chapter Two, you still believe in morality: you’re using philosophy to try to be as moral as possible. In Chapter Three, you’re starting to wonder if “morality” is even real. Maybe it’s just a sham, the illusion of a limitation that keeps you from getting what you really want. You need to bust that illusion and break those limitations, because you want to be happy, and being happy means getting what you want.

In Chapter Four the main idea was that if you keep going farther, then you have to wonder whether “what you want” is just as much of an illusion as “morality.” So now you’re even further away from Normal World. Maybe you don’t believe in normal rules anymore; that’s all just shadows on the cave wall. But maybe now you don’t believe in “normal” desires, either. Those are also shadows. And you want to get rid of those shadows, because you want to be happy. So if you want to get rid of those shadows, those “socially constructed” desires, maybe you’re going to have to discover and follow some new rules. You might be back to believing in “morality,” even though it won’t be “normal.”

Now: what do you notice about this way of understanding philosophy? Seems like “escape” is a common theme. In Chapter Two you’re escaping from your reactions, by reflecting on them. You’re slowing down your thinking so that you can exercise more choice about how your react, so that you can react in the right way, so that you can be happier. In Chapter Three you’re escaping from the idea that being “happy” requires “doing the right thing,” when maybe it actually requires “getting what you want” (by doing the wrong thing, if necessary). In Chapter Four you’re escaping from the idea that “what you want” is actually what you want in the first place. Seems like you’re always pursuing freedom for the sake of happiness.

As you continue to read, as you keep practicing the Basic Move during class discussions, it will help if you treat these two words — freedom and happiness — as the keys to the kingdom. The two key concepts. What you’re really trying to do, when you’re doing philosophy, is to become free and happy.

But here’s one of the things that philosophers are always doing, when they’re doing philosophy. They define their terms.

First lesson: the dictionary is not your friend. Dictionaries tell you how most people tend to use a word. But philosophers decide how they are going to use words, and often they use them in ways that most people don’t. Now, philosophers are also trying to communicate with those other people, so they have to be reasonable. But the basic point stands: philosophers aren’t interested in how most people use a word. They’re interested in how you are using a word. (A good rule of thumb for philosophy papers is “don’t cite the dictionary.”)

You might think this makes it easier. In fact, it makes it harder. Within reason, you can define your terms as you like, but the flip side is you are responsible for defining them clearly and precisely. And then you’re accountable for how you use the word, based on how you defined it at the beginning.

Of course this doesn’t apply to every word you speak or write. This is about your key words. First, you have to make sure you know what your key words are . (Usually it is pretty obvious, but sometimes, a term might be more important to your argument than you realized at first, and you’ll need to go back and define it.) Usually your key words are going to be ambiguous – they already have more than one meaning, before you even start to think about what you mean by them. In philosophy, the most important words are usually the ones that stand for the most complex ideas.

Take these two words, “freedom” and “happiness.” If freedom is something you’re looking for, then it matters very much what you have in mind. You and I might be looking for something we both call “freedom,” but what you have in mind is very different from what I have in mind. Same with happiness.

I am going to offer two different meanings for each term. You should keep these alternatives in your mind as you keep reading and thinking and talking.

For happiness, I want you to think of “Happiness One” versus “Happiness Two.” Happiness One is what you have in mind when you say “I feel happy right now.” It’s a passing feeling: you’re doing something you like, you’re being entertained, you’re excited, you’re not bored, whatever. It’s a feeling, and it’s pleasant, and it’s temporary. (Sometimes when people imagine a Utopia, they imagine it as a world in which it’s all Happiness One, all the time: a world in which it’s become permanent, not temporary.)

Happiness Two is what you have in mind when you think about someone you admire, who’s about to die, and you say “they lived a good life” or “they had no regrets.” Where Happiness One is a passing feeling, Happiness Two is a whole lifetime, which is composed of many different feelings: ups and downs, good and bad, pleasant and unpleasant. It’s more complex than Happiness One. It includes sadness and loss, struggle, maybe even suffering.

For freedom, I want you to think of “Negative Freedom” versus “Positive Freedom.”

Negative Freedom is not the “absence of freedom.” (Sometimes the terminology here is a bit confusing.) Negative Freedom means the absence of obstacles to getting what you want. If you’re in prison, you don’t have much Negative Freedom, because there are obstacles: guards, bars on the windows, razor wire. Laws and rules also take away Negative Freedom, because they lay down consequences: if you do this, then you’ll go to prison.

Positive freedom means the ability to do what is good for you. If you’re addicted to meth, you don’t have much Positive Freedom, because your addiction keeps you from holding down a job, eating good food, getting enough sleep, or whatever it might be. Suppose that meth is legal and it’s what you want and nothing is stopping you from walking across the street to get what you want. Then you have Negative Freedom. But at the same time you don’t have Positive Freedom because wanting meth makes you unable to do what is good for you.

The two types of happiness and the two types of freedom are not going to show up explicitly in the following chapters, or not very often at least: an occasional mention here and there is all you’ll get. Instead, you should keep them in the back of your mind and try to make the connections for yourself. What kind of freedom is Neo offering at the end of the Matrix? What kind of happiness do you find when you get outside the cave?

You should also be thinking about how the two kinds of freedom and the two kinds of happiness might be related to each other. What kind of happiness do you have when you have Negative Freedom, as opposed to Positive Freedom?

And, finally, you should be thinking about which kind of happiness and which kind of freedom — or perhaps some combination, or third alternative (remember: philosophers don’t like to accept that “there are just two choices”) — is the proper aim of life in general, and of a philosophical life in particular. What should you aim at, as a human being? And what does philosophy help you to aim at?

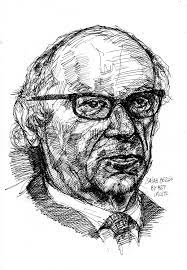

The distinction between “negative” and “positive” freedom comes from a philosopher named Isaiah Berlin. You can

The distinction between “negative” and “positive” freedom comes from a philosopher named Isaiah Berlin. You can