1 Boxes

What Keeps Me Here?

The Fifth Chapter,

in which you ask yourself

What Keeps Me Here?

Preparation

Required Reading: Don Ross, “The Elephant as a Person” (Aeon)

Optional Reading: “Why philosophers say chimps have to be considered persons” (Big Think,)

Writing:

- Ross’s key term is “person.” How does he define it? Answer with paraphrase, not quotation.

- An argument is a thesis supported by one or more reasons. What is Ross’s thesis? What reason(s) does he provide in support of his thesis? Paraphrase or quote briefly.

- What is your immediate reaction to Ross’s argument? Agreement, disagreement, or something else?

- Respond to the following question by writing at least one paragraph: If some kinds of animals are persons, should they have rights?

Introduction

So: the Big Ethical Question is how should I live? But one of the first things you notice is that you live with other people, who are also asking the same question, and answering it in all kinds of different ways. The Big Ethical Question leads straight the Big Political Question, which is how should we live together? Now you are doing political philosophy.

As soon as you start asking the question how should we live together? you start thinking about how people actually do live together, in society as it really is. If you want to move from how it is, to how it should be, you have to first understand how it is, and why. You have to understand Normal World.

Normal World is always like this: some people are on top, some are on bottom. Some people lead, others follow. Some people rule, others obey. In reality, there’s always hierarchy — just like there’s always a hierarchy in the cave. This is the situation.

What is your reaction?

Of course, there are different versions of the situation. There are variations on the scenario. Now, sometimes the hierarchy is soft and subtle — maybe in a “democracy” things are more spread out, everybody has a chance to be the ruler, to run for president, so it doesn’t feel oppressive, it feels right and good. Other times it’s hard and obvious, like in a dictatorship, where it feels downright evil.

And this isn’t just a question about “society” in the big sense. It’s a question you can ask about any human relationship, at any scale. Why is that person team captain and you aren’t? Why are some people popular and others aren’t? Why are some people bullies and others victims? Why is your “friend” always making you feel less-than — and why do you take it? Or maybe you’re the team captain, you’re the popular one, you’re the bully, you’re the “friend.” Why are you on top?

This is a question about power: who has it and who doesn’t, and how it got that way. When we ask how should we live together? we’re asking who should have the power? If we think we’re living together in the wrong way, if we think the wrong people have the power, then maybe we want to change things. So then you’re talking about “social justice,” reform and revolution, politics. But if you want to change things, you have to understand why they are they way they are; you have to understand what’s causing the problem if you’re going to fix it. You have to understand who has the power and why. Why some people are prisoners, and others are puppeteers. Why some are slaves, and others are masters.

Now you are going to read a short section from another very famous contribution to the philosophical conversation. It comes a book called Phenomenology of Spirit, by a German philosopher named Georg Hegel. The original passage is often referred to as “the master-slave dialectic.” It’s a story that tries to explain why some people become slaves, and others become masters. It’s a story that tries to explain the social situation in Normal World.

Don’t worry to much if this reading goes over your head. It’s one of the most difficult arguments in the history of philosophy, and some of the greatest philosophers have struggled to understand it. But it is still good to try: if anything, it will give you a sense for how complex philosophical thinking can be.

After you read Hegel’s words, you can go on to the next section, which explains the argument in simpler language.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, “Lordship and Bondage,” sections 178, & 186-196, from Phenomenology of Spirit

178. Self-consciousness exists as being in and being for itself inasmuch, and only inasmuch, as it exists in and for itself for another, i.e. inasmuch as it is acknowledged. It is therefore essentially one only in duplication, and reveals itself in a number of traits which have to be kept firmly apart, and yet reveal themselves as always melting into one another, and dissolving this apartness.

178. Self-consciousness exists as being in and being for itself inasmuch, and only inasmuch, as it exists in and for itself for another, i.e. inasmuch as it is acknowledged. It is therefore essentially one only in duplication, and reveals itself in a number of traits which have to be kept firmly apart, and yet reveal themselves as always melting into one another, and dissolving this apartness.

186. Self-consciousness is at first simple being-for-self which is attached to an immediate individuality which excludes all others from itself. Self at first confronts self, not as an infinite negation of the negation making all its own, but as a simple case of natural being facing another such case, both deeply absorbed in the business of living. Each is conscious only of its own being, and so has no true certainty of itself, since the being of the self is essentially a socially acknowledged being.

187. Self- consciousness must, however, express itself as the negation of all mere objectivity and particularity. This initially takes the form of desiring the death of the other at the risk of its own life. Self consciousness must be willing to sacrifice everything concrete for its own infinite self-respect and the similar respect of all others. A life-and-death struggle therefore ensues between the two rival self-consciousnesses.

188. For both members to die in the life-and-death struggle would not, however, resolve the tension between them. (nor would the death of one of them do it.) Death certainly eliminates all opposition, but only for others, or in a ‘dead’ manner. Death does not preserve the struggle that it eliminates in and for the parties in question. For the preservation, it is essential that the parties in question should live.

189. The demotion of another self-consciousness so that it does not really compete with my self-consciousness, now takes the new form of making it thinglike and dependent, the self consciousness of a slave as opposed to that of a master. That the two self-consciousnesses are at bottom the same becomes deeply veiled.

190. The self-consciousness of the master is essentially related to the being of the mere things he uses and uses up, and these he enjoys through the slave’s self-consciousness. The slave prepares and arranges things for the enjoyment of the master. The self-consciousness of the master is likewise essentially related to the self-consciousness of the slave through the various punitive, constraining, and rewarding instruments which keep the slave enslaved. The slave working on things does not completely overcome their thingness, since they do not become what he wishes them to be or not for himself. It is the master who reaps the enjoyment from the slave’s labours.

191. We thus achieve an essentially unbalanced relation in which the slave altogether gives up his being-for-self in the favour of the master. The master uses the slave as an instrument to control the thing for its own (the master’s) purposes, and not for the slave’s, and the slave acquiesces to the situation. This means that his self-consciousness demands from a consciousness so degraded and distorted. What the master sees in the slave, or what the slave sees in the master is not what either sees in himself.

192. The master therefore paradoxically depends for his masterhood on the slave’s self-consciousness, and entirely fails of the fully realized independence of status which his self-consciousness demands.

193. The truth of independent self-consciousness is therefore to be found rather in the slave’s self-consciousness than in the master’s. Each is therefore the inverse of what it immediately and superficially is given as being.

194. The slave in his fearful respect for the master becomes shaken out of his narrow self-identifications and self-interest and rises to the absolute negativity, the disinterested all-embracingness of true self consciousness. He becomes the ideal which he contemplates in his master.

195. The slave has the further advantage that in working on the object he as it were preserves his labour, makes the outward thing his own and puts himself into it, whereas the master’s dealings with the object end in vanishing enjoyments. The slave overcomes the otherness and mere existence of material thinghood more thoroughly than the master, and so achieves a more genuine selfconsciousness.

196. The slave in overcoming the mere existence of material thinghood also rises above the fear which was his first reaction to absolute otherness as embodied in the master. Then he achieved self-consciousness in opposition to such otherness, now he achieves a self-consciousness not opposed to otherness, but which discovers itself in otherness. In shaping the thing creatively, he becomes aware of his own boundless originality. Hegel thinks that the discipline of service and obedience is essential to self-consciousness: mere mastery of things alone would not yield to it. Only the discipline of service enables the conscious being to master himself, i.e. his finite, contingent, natural self. Without this discipline formative ability would degenerate into narrow cleverness placed at the service of personal self-will.

Discussion

Envision yourself dreaming. In your dream you encounter another person. She approaches you. You believe that this other person is real. That’s what it is to dream, after all: it’s to believe that the dreamworld is the real world. Once you know it’s a dreamworld, the dream is over. the So you believe the dreamperson is a real person, a separate consciousness. You believe she is an individual with her own mind, not a figment of your mind.

When you wake up, you realize that all along this person was just — you. She was not a separate consciousness; she was a projection of your own consciousness. And, if you care to reflect on your dream, to try to understand it, you might see that the dreamperson was not exactly “you,” but was more like a symbol of something else: your own fears, your own desires, your own worries, your own ideas, your own preoccupations.

Now envision yourself awake, in the real world. Your normal world. In your normal world you encounter another person. You believe this other person is real — but what exactly does “real” mean to you? The person approaches you, and you feel fear, or desire, or worry. You say he is “real,” but what is really real for you are those feelings. What is real is your idea of who he really is. What is real is what he symbolizes for you. All you see is what you want. You do not see “him” at all. You see your dream-version of him. It might be a daydream or a nightmare: it is an illusion either way. He is not real for you, even though you believe he is real.

You are walking around, looking alive, but you are stuck in your head, as if you are dead. You are dreaming that you are awake. This must be the hardest kind of dream to wake up from. Unimaginably hard.

But suppose something wakes you up. Maybe it is a dramatic event, an unexpected call, a sudden revelation. Maybe it is a question you had never asked before, a story, an image, a metaphor, a book or a song or a film. Maybe it is this slowed-down process of thinking, this relaxed wandering around your mind. Maybe it is a long conversation. Maybe it is philosophy. Or maybe it just is a random encounter on the street.Whatever it is, what happens first is this: you start to see yourself through another person’s eyes.

You can look at a dreamperson, but a dreamperson cannot look back at you. Once you realize that she is looking back at you, you realize that she is like you, since she can do what you can do: she can look back. You have been putting her in a box. As soon as you realize that she has been doing the same thing to you, that she has been putting you in a box, you realize she is capable of doing the same thing to you. That shows you that she is not a dream. And this also wakes you up from your dream. It shows you who you really are.

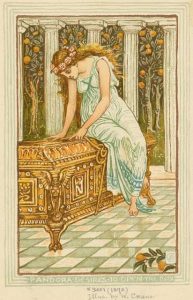

But now things get interesting. Because you do not want to wake up from your dream. (This is why it is the hardest kind of dream to escape.) After all, in your dream you have a magical power. You have the power to put other people in the boxes you make for them. You put them inside those boxes, and then the boxes are all you see. And boxes are things, not people. Boxes do not look back, or talk back. If a box is in your way, move it. If a box is broken, get rid of it. Boxes do not want anything. If you are the only real person in a world of boxes, then your desires are the only desires in the world. And if you are smart and strong enough to move the boxes where you want them, or to destroy them when you don’t want them anymore, then this is a world where you get everything you want.

And the other person is in the same position! She lives in the same kind of dreamworld, where she is the only real person and you are just a box. When she catches a glimpse of herself through your eyes, she realizes she is not the only person, that since you can look back at her, you must be more than a box. So you are a threat to her, and she is a threat to you.

Here is the situation: it is very tricky. You want her to see you as a person, not a box. So you want to secure her respect. At the same time you want to see her as a box, not a person. So you want to fulfill your desires. But you cannot have both. You can do what you want with a box; but a box cannot give you respect. If you want her to see you as a person, then she will have to be a person, since boxes cannot see anything. But if she is a person, then she is not a box, and that means you cannot just do what you want with her. And remember: she is in exactly the same position. She wants you to be a person, so she can secure your respect; but she also wants you to be a box, so your own desires do not interfere with hers.

Both of you want to wake up from the dream and enter the real world, where people respect each other as equals. But both of you also want to stay in the dreamworld, where you don’t have to deal with the limits on your desires that come with respecting other people’s desires.

Most of the time, no one wakes up. What happens instead is this: you fight. There is a battle inside the dreamworld. One of you wins, and the other loses. And this is where “power structures” come from. The winner becomes the master; the loser becomes the slave, and everybody gets used to it. The dream goes on.

What are you fighting for? You are fighting to put the other person in a box. You want to turn the other person into a slave: a tool, a thing you use to get what you want. You want to be the master. At the same time you are fighting to keep the other person from putting you in a box, making you the slave. You want to force the other person to respect you, to see you as a person. But remember: you can’t have both. A tool can’t see anything. A tool can’t give you the respect you want.

So if you win, you lose. You lose the respect you wanted. You lose the chance to wake up from your dream. You trade your chance to wake up as a person in the real world for a chance to become a master in the dreamworld. You trade the real world for a daydream.

What happens if you lose? This is maybe even more interesting: in a sense, if you lose, you win. The slave no longer gets what he wants: he is a tool that serves the wants of the master. And this is a terrible thing. It is a nightmare. But it also teaches the slave something that the master can no longer know. It teaches him that he is more than a bundle of desires. To serve the master, the slave must master his own desires: and this teaches the slave self-mastery. Meanwhile, the master never has to master himself at all. The master becomes empty, less and less of a real person, because he never has to work. But the slave becomes more and more real while working for the master. While the master has power over the slave, the slave gains a power over himself. While the master sinks deeper into his daydream of power, the slave gains the power, slowly, to wake up from his nightmare of powerlessness.

(Remember Epictetus? “We react not to the things themselves but to our judgments about the things.” That’s about mastering yourself. Control your response to the situation by controlling the judgment that leads to your response. So it’s interesting to realize that Epictetus was a slave.)

And after all, which kind of dream is easier to want to escape: a daydream in which you get everything you want and feel like you deserve it, or a nightmare in which you get nothing, and feel like you’re nothing?

Eventually, the master becomes so weakened, and the slave becomes so awakened, that the slave is ready to confront the master. And then, it happens all over again. Back to where it started. There is another fight. There are words for this kind of fight. On the small scale: “standing up to the bully.” On the grand scale: Revolution.

But once again, what happens most of the time is this: no one really wakes up, at least not for good. Most of the time, the master and the slave just switch places. The dreamworld of power remains intact. And the question — the question of political philosophy — is whether it will ever be any different, whether it can be any different. Can we wake up to a real world in which people treat each other as equals, as more than the boxes we make for each other? Or is that kind of real world itself . . . nothing but an impossible dream?

Reflection

- What is one “box” that people put you in?

- What is one “box” that you put other people in?

- People often identify themselves by referring to groups. (“I am a white male”; “as a black woman”; etc). Would Hegel say this is good, bad, or a little of both? What might be good and what might be bad about seeing yourself this way?