13 Woods

The Thirteenth Chapter,

in which you ask yourself

“How do I get out?”

Preparation

Required Reading: Westacott, “Why the simple life is not just beautiful, it’s necessary” (Aeon)

Optional Reading: Ellis, “Philosophy cannot resolve the question, ‘How should we live?’” (Aeon)

Writing:

- Westacott’s key term is “the simple life.” How does he seem to understand it? Answer with paraphrase, not quotation.

- An argument is a thesis supported by one or more reasons. What is — thesis? What reason(s) does he provide in support of his thesis? Paraphrase or quote briefly.

- What is your immediate reaction to Westacott’s argument? Agreement, disagreement, or something else?

- Respond to the following question by writing at least 250 words: The simple life might be the best life, and it might become “necessary” for the reasons Westacott says. But what would “living simply” actually look like, in your own particular circumstances? What would you have to start doing, or stop doing? What small changes would you need to make. What radical changes?

Introduction

Ever been camping in the woods and thought, “what if I never went back?” Even if it was just for a second. Probably you dismissed the thought right away. Impractical, what would you eat, you don’t know how to survive, what about bugs, there might be bears. Still: you thought about it. Why? What was in the woods that made you think about staying there? What was in the woods that made you think about leaving here — leaving normal world?

Well, it wasn’t “comfort.” It wasn’t “security.” The woods doesn’t offer those. A certain kind of freedom, maybe? A certain kind of happiness? Maybe a kind of freedom or happiness that you suddenly realized — if only for a second — wasn’t available back in normal world. You saw, just for a second, that normal world is not the only world. That there are other options, there are trade-offs, and maybe you’d never really counted the costs, never really made a choice.

And then it’s over. You go back to Normal World. You forget what you realized. You go to work, you go to class, you go watch Netflix. This is normal. Going off to live in the woods would not be normal. Got to be normal.

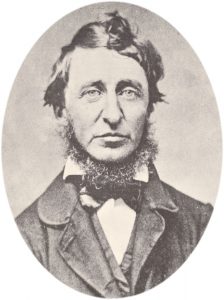

Henry David Thoreau wasn’t normal. Another strange person, like Simone Weil. Unlike her, kind of a jerk. At least some people say so. Thoreau is always telling everyone that they’re not living authentically, that they’re accepting “normal” when life could be so much better than normal. He’s always yelling, “you must change your life!” And he seems to think the Simone Weil route won’t do for most people. Someone like her, with her incredible ability to pay attention, to do things for their own sake without getting distracted, might be able to stay in school without getting schooled. But most people, if they’re really going to learn how to pay attention, how to live life for its own sake — they’re actually going to have to eliminate the distractions. Most of us aren’t strong enough to just ignore the shadows. We have to go to where there are no shadows. We actually have to drop out, if we want to deprogram ourselves. We’re not going to be able to live differently, to live philosophically, unless we literally leave the cave. We’ve got to leave the society that nurtured us and get back to nature. At least for a while: long enough to get past society’s illusions about what’s worth wanting, so we can see clearly what is worth wanting.

That’s what Thoreau did. Went off to the woods, by himself, for two years. Built his own house, grew his own food. Wrote his own book. Which you’re now going to read (parts of it). A very famous book called Walden, which is the name of the pond where he lived in solitude.

Thoreau literally walks away. What dos his solitude allow him to see that we can’t see, or can’t see as clearly? What could solitude show you?

What if you tried it?

Henry David Thoreau, Walden (Selections)

When I wrote the following pages, or rather the bulk of them, I lived alone, in the woods, a mile from any neighbor, in a house which I had built myself, on the shore of Walden Pond, in Concord, Massachusetts, and earned my living by the labor of my hands only. I lived there two years and two months. At present I am a sojourner in civilized life again.

When I wrote the following pages, or rather the bulk of them, I lived alone, in the woods, a mile from any neighbor, in a house which I had built myself, on the shore of Walden Pond, in Concord, Massachusetts, and earned my living by the labor of my hands only. I lived there two years and two months. At present I am a sojourner in civilized life again.

I should not obtrude my affairs so much on the notice of my readers if very particular inquiries had not been made by my townsmen concerning my mode of life, which some would call impertinent, though they do not appear to me at all impertinent, but, considering the circumstances, very natural and pertinent. Some have asked what I got to eat; if I did not feel lonesome; if I was not afraid; and the like. Others have been curious to learn what portion of my income I devoted to charitable purposes; and some, who have large families, how many poor children I maintained. I will therefore ask those of my readers who feel no particular interest in me to pardon me if I undertake to answer some of these questions in this book. In most books, the I, or first person, is omitted; in this it will be retained; that, in respect to egotism, is the main difference. We commonly do not remember that it is, after all, always the first person that is speaking. I should not talk so much about myself if there were anybody else whom I knew as well. Unfortunately, I am confined to this theme by the narrowness of my experience. Moreover, I, on my side, require of every writer, first or last, a simple and sincere account of his own life, and not merely what he has heard of other men’s lives; some such account as he would send to his kindred from a distant land; for if he has lived sincerely, it must have been in a distant land to me. Perhaps these pages are more particularly addressed to poor students. As for the rest of my readers, they will accept such portions as apply to them. I trust that none will stretch the seams in putting on the coat, for it may do good service to him whom it fits.

…. .

Most men, even in this comparatively free country, through mere ignorance and mistake, are so occupied with the factitious cares and superfluously coarse labors of life that its finer fruits cannot be plucked by them. Their fingers, from excessive toil, are too clumsy and tremble too much for that. Actually, the laboring man has not leisure for a true integrity day by day; he cannot afford to sustain the manliest relations to men; his labor would be depreciated in the market. He has no time to be anything but a machine. How can he remember well his ignorance—which his growth requires—who has so often to use his knowledge? We should feed and clothe him gratuitously sometimes, and recruit him with our cordials, before we judge of him. The finest qualities of our nature, like the bloom on fruits, can be preserved only by the most delicate handling. Yet we do not treat ourselves nor one another thus tenderly.

Some of you, we all know, are poor, find it hard to live, are sometimes, as it were, gasping for breath. I have no doubt that some of you who read this book are unable to pay for all the dinners which you have actually eaten, or for the coats and shoes which are fast wearing or are already worn out, and have come to this page to spend borrowed or stolen time, robbing your creditors of an hour. It is very evident what mean and sneaking lives many of you live, for my sight has been whetted by experience; always on the limits, trying to get into business and trying to get out of debt, a very ancient slough, called by the Latins aes alienum, another’s brass, for some of their coins were made of brass; still living, and dying, and buried by this other’s brass; always promising to pay, promising to pay, tomorrow, and dying today, insolvent; seeking to curry favor, to get custom, by how many modes, only not state-prison offenses; lying, flattering, voting, contracting yourselves into a nutshell of civility or dilating into an atmosphere of thin and vaporous generosity, that you may persuade your neighbor to let you make his shoes, or his hat, or his coat, or his carriage, or import his groceries for him; making yourselves sick, that you may lay up something against a sick day, something to be tucked away in an old chest, or in a stocking behind the plastering, or, more safely, in the brick bank; no matter where, no matter how much or how little.

I sometimes wonder that we can be so frivolous, I may almost say, as to attend to the gross but somewhat foreign form of servitude called Negro Slavery, there are so many keen and subtle masters that enslave both North and South. It is hard to have a Southern overseer; it is worse to have a Northern one; but worst of all when you are the slave-driver of yourself. Talk of a divinity in man! Look at the teamster on the highway, wending to market by day or night; does any divinity stir within him? His highest duty to fodder and water his horses! What is his destiny to him compared with the shipping interests? Does not he drive for Squire Make-a-stir? How godlike, how immortal, is he? See how he cowers and sneaks, how vaguely all the day he fears, not being immortal nor divine, but the slave and prisoner of his own opinion of himself, a fame won by his own deeds. Public opinion is a weak tyrant compared with our own private opinion. What a man thinks of himself, that it is which determines, or rather indicates, his fate. Self-emancipation even in the West Indian provinces of the fancy and imagination—what Wilberforce is there to bring that about? Think, also, of the ladies of the land weaving toilet cushions against the last day, not to betray too green an interest in their fates! As if you could kill time without injuring eternity.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of mankind. There is no play in them, for this comes after work. But it is a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things.

When we consider what, to use the words of the catechism, is the chief end of man, and what are the true necessaries and means of life, it appears as if men had deliberately chosen the common mode of living because they preferred it to any other. Yet they honestly think there is no choice left. But alert and healthy natures remember that the sun rose clear. It is never too late to give up our prejudices. No way of thinking or doing, however ancient, can be trusted without proof. What everybody echoes or in silence passes by as true to-day may turn out to be falsehood to-morrow, mere smoke of opinion, which some had trusted for a cloud that would sprinkle fertilizing rain on their fields. What old people say you cannot do, you try and find that you can. Old deeds for old people, and new deeds for new. Old people did not know enough once, perchance, to fetch fresh fuel to keep the fire a-going; new people put a little dry wood under a pot, and are whirled round the globe with the speed of birds, in a way to kill old people, as the phrase is. Age is no better, hardly so well, qualified for an instructor as youth, for it has not profited so much as it has lost. One may almost doubt if the wisest man has learned anything of absolute value by living. Practically, the old have no very important advice to give the young, their own experience has been so partial, and their lives have been such miserable failures, for private reasons, as they must believe; and it may be that they have some faith left which belies that experience, and they are only less young than they were. I have lived some thirty years on this planet, and I have yet to hear the first syllable of valuable or even earnest advice from my seniors. They have told me nothing, and probably cannot tell me anything to the purpose. Here is life, an experiment to a great extent untried by me; but it does not avail me that they have tried it. If I have any experience which I think valuable, I am sure to reflect that this my Mentors said nothing about.

…. .

The greater part of what my neighbors call good I believe in my soul to be bad, and if I repent of anything, it is very likely to be my good behavior. What demon possessed me that I behaved so well? You may say the wisest thing you can, old man—you who have lived seventy years, not without honor of a kind—I hear an irresistible voice which invites me away from all that. One generation abandons the enterprises of another like stranded vessels.

… .

Granted that the majority are able at last either to own or hire the modern house with all its improvements. While civilization has been improving our houses, it has not equally improved the men who are to inhabit them. It has created palaces, but it was not so easy to create noblemen and kings. And if the civilized man’s pursuits are no worthier than the savage’s, if he is employed the greater part of his life in obtaining gross necessaries and comforts merely, why should he have a better dwelling than the former?

But how do the poor minority fare? Perhaps it will be found that just in proportion as some have been placed in outward circumstances above the savage, others have been degraded below him. The luxury of one class is counterbalanced by the indigence of another. On the one side is the palace, on the other are the almshouse and “silent poor.” The myriads who built the pyramids to be the tombs of the Pharaohs were fed on garlic, and it may be were not decently buried themselves. The mason who finishes the cornice of the palace returns at night perchance to a hut not so good as a wigwam. It is a mistake to suppose that, in a country where the usual evidences of civilization exist, the condition of a very large body of the inhabitants may not be as degraded as that of savages. I refer to the degraded poor, not now to the degraded rich. To know this I should not need to look farther than to the shanties which everywhere border our railroads, that last improvement in civilization; where I see in my daily walks human beings living in sties, and all winter with an open door, for the sake of light, without any visible, often imaginable, wood-pile, and the forms of both old and young are permanently contracted by the long habit of shrinking from cold and misery, and the development of all their limbs and faculties is checked. It certainly is fair to look at that class by whose labor the works which distinguish this generation are accomplished. Such too, to a greater or less extent, is the condition of the operatives of every denomination in England, which is the great workhouse of the world. Or I could refer you to Ireland, which is marked as one of the white or enlightened spots on the map. Contrast the physical condition of the Irish with that of the North American Indian, or the South Sea Islander, or any other savage race before it was degraded by contact with the civilized man. Yet I have no doubt that that people’s rulers are as wise as the average of civilized rulers. Their condition only proves what squalidness may consist with civilization. I hardly need refer now to the laborers in our Southern States who produce the staple exports of this country, and are themselves a staple production of the South. But to confine myself to those who are said to be in moderate circumstances.

Most men appear never to have considered what a house is, and are actually though needlessly poor all their lives because they think that they must have such a one as their neighbors have. As if one were to wear any sort of coat which the tailor might cut out for him, or, gradually leaving off palm-leaf hat or cap of woodchuck skin, complain of hard times because he could not afford to buy him a crown! It is possible to invent a house still more convenient and luxurious than we have, which yet all would admit that man could not afford to pay for. Shall we always study to obtain more of these things, and not sometimes to be content with less? Shall the respectable citizen thus gravely teach, by precept and example, the necessity of the young man’s providing a certain number of superfluous glow-shoes, and umbrellas, and empty guest chambers for empty guests, before he dies? Why should not our furniture be as simple as the Arab’s or the Indian’s? When I think of the benefactors of the race, whom we have apotheosized as messengers from heaven, bearers of divine gifts to man, I do not see in my mind any retinue at their heels, any carload of fashionable furniture. Or what if I were to allow—would it not be a singular allowance?—that our furniture should be more complex than the Arab’s, in proportion as we are morally and intellectually his superiors! At present our houses are cluttered and defiled with it, and a good housewife would sweep out the greater part into the dust hole, and not leave her morning’s work undone. Morning work! By the blushes of Aurora and the music of Memnon, what should be man’s morning work in this world? I had three pieces of limestone on my desk, but I was terrified to find that they required to be dusted daily, when the furniture of my mind was all undusted still, and threw them out the window in disgust. How, then, could I have a furnished house? I would rather sit in the open air, for no dust gathers on the grass, unless where man has broken ground.

…. .

One young man of my acquaintance, who has inherited some acres, told me that he thought he should live as I did, if he had the means. I would not have any one adopt my mode of living on any account; for, beside that before he has fairly learned it I may have found out another for myself, I desire that there may be as many different persons in the world as possible; but I would have each one be very careful to find out and pursue his own way, and not his father’s or his mother’s or his neighbor’s instead. The youth may build or plant or sail, only let him not be hindered from doing that which he tells me he would like to do. It is by a mathematical point only that we are wise, as the sailor or the fugitive slave keeps the polestar in his eye; but that is sufficient guidance for all our life. We may not arrive at our port within a calculable period, but we would preserve the true course.

Undoubtedly, in this case, what is true for one is truer still for a thousand, as a large house is not proportionally more expensive than a small one, since one roof may cover, one cellar underlie, and one wall separate several apartments. But for my part, I preferred the solitary dwelling. Moreover, it will commonly be cheaper to build the whole yourself than to convince another of the advantage of the common wall; and when you have done this, the common partition, to be much cheaper, must be a thin one, and that other may prove a bad neighbor, and also not keep his side in repair. The only co-operation which is commonly possible is exceedingly partial and superficial; and what little true co-operation there is, is as if it were not, being a harmony inaudible to men. If a man has faith, he will co-operate with equal faith everywhere; if he has not faith, he will continue to live like the rest of the world, whatever company he is joined to. To co-operate in the highest as well as the lowest sense, means to get our living together. I heard it proposed lately that two young men should travel together over the world, the one without money, earning his means as he went, before the mast and behind the plow, the other carrying a bill of exchange in his pocket. It was easy to see that they could not long be companions or co-operate, since one would not operate at all. They would part at the first interesting crisis in their adventures. Above all, as I have implied, the man who goes alone can start today; but he who travels with another must wait till that other is ready, and it may be a long time before they get off.

… .

Every morning was a cheerful invitation to make my life of equal simplicity, and I may say innocence, with Nature herself. I have been as sincere a worshipper of Aurora as the Greeks. I got up early and bathed in the pond; that was a religious exercise, and one of the best things which I did. They say that characters were engraven on the bathing tub of King Tchingthang to this effect: “Renew thyself completely each day; do it again, and again, and forever again.” I can understand that. Morning brings back the heroic ages. I was as much affected by the faint hum of a mosquito making its invisible and unimaginable tour through my apartment at earliest dawn, when I was sitting with door and windows open, as I could be by any trumpet that ever sang of fame. It was Homer’s requiem; itself an Iliad and Odyssey in the air, singing its own wrath and wanderings. There was something cosmical about it; a standing advertisement, till forbidden, of the everlasting vigor and fertility of the world. The morning, which is the most memorable season of the day, is the awakening hour. Then there is least somnolence in us; and for an hour, at least, some part of us awakes which slumbers all the rest of the day and night. Little is to be expected of that day, if it can be called a day, to which we are not awakened by our Genius, but by the mechanical nudgings of some servitor, are not awakened by our own newly acquired force and aspirations from within, accompanied by the undulations of celestial music, instead of factory bells, and a fragrance filling the air—to a higher life than we fell asleep from; and thus the darkness bear its fruit, and prove itself to be good, no less than the light. That man who does not believe that each day contains an earlier, more sacred, and auroral hour than he has yet profaned, has despaired of life, and is pursuing a descending and darkening way. After a partial cessation of his sensuous life, the soul of man, or its organs rather, are reinvigorated each day, and his Genius tries again what noble life it can make. All memorable events, I should say, transpire in morning time and in a morning atmosphere. The Vedas say, “All intelligences awake with the morning.” Poetry and art, and the fairest and most memorable of the actions of men, date from such an hour. All poets and heroes, like Memnon, are the children of Aurora, and emit their music at sunrise. To him whose elastic and vigorous thought keeps pace with the sun, the day is a perpetual morning. It matters not what the clocks say or the attitudes and labors of men. Morning is when I am awake and there is a dawn in me. Moral reform is the effort to throw off sleep. Why is it that men give so poor an account of their day if they have not been slumbering? They are not such poor calculators. If they had not been overcome with drowsiness, they would have performed something. The millions are awake enough for physical labor; but only one in a million is awake enough for effective intellectual exertion, only one in a hundred millions to a poetic or divine life. To be awake is to be alive. I have never yet met a man who was quite awake. How could I have looked him in the face?

We must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn, which does not forsake us in our soundest sleep. I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor. It is something to be able to paint a particular picture, or to carve a statue, and so to make a few objects beautiful; but it is far more glorious to carve and paint the very atmosphere and medium through which we look, which morally we can do. To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of arts. Every man is tasked to make his life, even in its details, worthy of the contemplation of his most elevated and critical hour. If we refused, or rather used up, such paltry information as we get, the oracles would distinctly inform us how this might be done.

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion. For most men, it appears to me, are in a strange uncertainty about it, whether it is of the devil or of God, and have somewhat hastily concluded that it is the chief end of man here to “glorify God and enjoy him forever.

Still we live meanly, like ants; though the fable tells us that we were long ago changed into men; like pygmies we fight with cranes; it is error upon error, and clout upon clout, and our best virtue has for its occasion a superfluous and evitable wretchedness. Our life is frittered away by detail. An honest man has hardly need to count more than his ten fingers, or in extreme cases he may add his ten toes, and lump the rest. Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand; instead of a million count half a dozen, and keep your accounts on your thumb-nail. In the midst of this chopping sea of civilized life, such are the clouds and storms and quicksands and thousand-and-one items to be allowed for, that a man has to live, if he would not founder and go to the bottom and not make his port at all, by dead reckoning, and he must be a great calculator indeed who succeeds. Simplify, simplify. Instead of three meals a day, if it be necessary eat but one; instead of a hundred dishes, five; and reduce other things in proportion. Our life is like a German Confederacy, made up of petty states, with its boundary forever fluctuating, so that even a German cannot tell you how it is bounded at any moment. The nation itself, with all its so-called internal improvements, which, by the way are all external and superficial, is just such an unwieldy and overgrown establishment, cluttered with furniture and tripped up by its own traps, ruined by luxury and heedless expense, by want of calculation and a worthy aim, as the million households in the land; and the only cure for it, as for them, is in a rigid economy, a stern and more than Spartan simplicity of life and elevation of purpose. It lives too fast. Men think that it is essential that the Nation have commerce, and export ice, and talk through a telegraph, and ride thirty miles an hour, without a doubt, whether they do or not; but whether we should live like baboons or like men, is a little uncertain. If we do not get out sleepers, and forge rails, and devote days and nights to the work, but go to tinkering upon our lives to improve them, who will build railroads? And if railroads are not built, how shall we get to heaven in season? But if we stay at home and mind our business, who will want railroads? We do not ride on the railroad; it rides upon us. Did you ever think what those sleepers are that underlie the railroad? Each one is a man, an Irishman, or a Yankee man. The rails are laid on them, and they are covered with sand, and the cars run smoothly over them. They are sound sleepers, I assure you. And every few years a new lot is laid down and run over; so that, if some have the pleasure of riding on a rail, others have the misfortune to be ridden upon. And when they run over a man that is walking in his sleep, a supernumerary sleeper in the wrong position, and wake him up, they suddenly stop the cars, and make a hue and cry about it, as if this were an exception. I am glad to know that it takes a gang of men for every five miles to keep the sleepers down and level in their beds as it is, for this is a sign that they may sometime get up again.

Why should we live with such hurry and waste of life? We are determined to be starved before we are hungry. Men say that a stitch in time saves nine, and so they take a thousand stitches today to save nine tomorrow. As for work, we haven’t any of any consequence. We have the Saint Vitus’ dance, and cannot possibly keep our heads still. If I should only give a few pulls at the parish bell- rope, as for a fire, that is, without setting the bell, there is hardly a man on his farm in the outskirts of Concord, notwithstanding that press of engagements which was his excuse so many times this morning, nor a boy, nor a woman, I might almost say, but would forsake all and follow that sound, not mainly to save property from the flames, but, if we will confess the truth, much more to see it burn, since burn it must, and we, be it known, did not set it on fire—or to see it put out, and have a hand in it, if that is done as handsomely; yes, even if it were the parish church itself. Hardly a man takes a half-hour’s nap after dinner, but when he wakes he holds up his head and asks, “What’s the news?” as if the rest of mankind had stood his sentinels. Some give directions to be waked every half-hour, doubtless for no other purpose; and then, to pay for it, they tell what they have dreamed. After a night’s sleep the news is as indispensable as the breakfast. “Pray tell me anything new that has happened to a man anywhere on this globe”—and he reads it over his coffee and rolls, that a man has had his eyes gouged out this morning on the Wachito River; never dreaming the while that he lives in the dark unfathomed mammoth cave of this world, and has but the rudiment of an eye himself.

… .

Shams and delusions are esteemed for soundest truths, while reality is fabulous. If men would steadily observe realities only, and not allow themselves to be deluded, life, to compare it with such things as we know, would be like a fairy tale and the Arabian Nights’ Entertainments. If we respected only what is inevitable and has a right to be, music and poetry would resound along the streets. When we are unhurried and wise, we perceive that only great and worthy things have any permanent and absolute existence, that petty fears and petty pleasures are but the shadow of the reality. This is always exhilarating and sublime. By closing the eyes and slumbering, and consenting to be deceived by shows, men establish and confirm their daily life of routine and habit everywhere, which still is built on purely illusory foundations. Children, who play life, discern its true law and relations more clearly than men, who fail to live it worthily, but who think that they are wiser by experience, that is, by failure. I have read in a Hindoo book, that “there was a king’s son, who, being expelled in infancy from his native city, was brought up by a forester, and, growing up to maturity in that state, imagined himself to belong to the barbarous race with which he lived. One of his father’s ministers having discovered him, revealed to him what he was, and the misconception of his character was removed, and he knew himself to be a prince. So soul,” continues the Hindoo philosopher, “from the circumstances in which it is placed, mistakes its own character, until the truth is revealed to it by some holy teacher, and then it knows itself to be Brahme.” I perceive that we inhabitants of New England live this mean life that we do because our vision does not penetrate the surface of things. We think that that is which appears to be. If a man should walk through this town and see only the reality, where, think you, would the “Mill-dam” go to? If he should give us an account of the realities he beheld there, we should not recognize the place in his description. Look at a meeting-house, or a court-house, or a jail, or a shop, or a dwelling-house, and say what that thing really is before a true gaze, and they would all go to pieces in your account of them. Men esteem truth remote, in the outskirts of the system, behind the farthest star, before Adam and after the last man. In eternity there is indeed something true and sublime. But all these times and places and occasions are now and here. God himself culminates in the present moment, and will never be more divine in the lapse of all the ages. And we are enabled to apprehend at all what is sublime and noble only by the perpetual instilling and drenching of the reality that surrounds us. The universe constantly and obediently answers to our conceptions; whether we travel fast or slow, the track is laid for us. Let us spend our lives in conceiving then. The poet or the artist never yet had so fair and noble a design but some of his posterity at least could accomplish it.

Let us spend one day as deliberately as Nature, and not be thrown off the track by every nutshell and mosquito’s wing that falls on the rails. Let us rise early and fast, or break fast, gently and without perturbation; let company come and let company go, let the bells ring and the children cry—determined to make a day of it. Why should we knock under and go with the stream? Let us not be upset and overwhelmed in that terrible rapid and whirlpool called a dinner, situated in the meridian shallows. Weather this danger and you are safe, for the rest of the way is down hill. With unrelaxed nerves, with morning vigor, sail by it, looking another way, tied to the mast like Ulysses. If the engine whistles, let it whistle till it is hoarse for its pains. If the bell rings, why should we run? We will consider what kind of music they are like. Let us settle ourselves, and work and wedge our feet downward through the mud and slush of opinion, and prejudice, and tradition, and delusion, and appearance, that alluvion which covers the globe, through Paris and London, through New York and Boston and Concord, through Church and State, through poetry and philosophy and religion, till we come to a hard bottom and rocks in place, which we can call reality, and say, This is, and no mistake; and then begin, having a point d’appui, below freshet and frost and fire, a place where you might found a wall or a state, or set a lamp-post safely, or perhaps a gauge, not a Nilometer, but a Realometer, that future ages might know how deep a freshet of shams and appearances had gathered from time to time. If you stand right fronting and face to face to a fact, you will see the sun glimmer on both its surfaces, as if it were a scimitar, and feel its sweet edge dividing you through the heart and marrow, and so you will happily conclude your mortal career. Be it life or death, we crave only reality. If we are really dying, let us hear the rattle in our throats and feel cold in the extremities; if we are alive, let us go about our business.

Discussion

Why does Thoreau leave normal world? Why does he walk away? The answer is now a famous phrase: “to live deliberately.”

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life. . .

Thoreau says to himself, “You must change your life.” So he does. He builds a room of his own. But this is a literal cabin in the woods — not a city in speech. Of course, he does make a city in speech (the words you just read) while he’s living in that cabin. But he needed the cabin to make the book.

Simone Weil can be “in the world, but not of the world.” She can “live deliberately” even while she’s surrounded by others who aren’t. But most people can’t do that. Most people aren’t mystics. Thoreau seemed to need actual solitude before he could learn to live deliberately — to live philosophically. Most people are probably more like Thoreau than Weil. Or, most people have to be like Thoreau, before they can be like Weil. Most of us need to literally withdraw from the world, if we’re going to be able to live differently in the world. Maybe not for two years at a time. But there are other, more modest approaches. Daily retreats, an hour in the morning, an hour in the evening. You don’t have to go live by Walden. But you do have to find time and space for something like the experience of Walden in your daily life.

Living deliberately, living philosophically: Thoreau makes this way of life all about freedom. Now, you remember that there are two kinds of freedom. Negative freedom, freedom-from, the ability to get what you want. Positive freedom, freedom-to, the ability to want what’s good. Strange still to think like that, isn’t it: strange to think that “wanting” is an “ability.” But it is! You learned, you were taught, how to want certain things, to fear certain things. You were schooled. So it must be possible to learn, to be taught, to want different things. That’s what Thoreau thinks: that it must be possible “to see if I could not learn what it had to teach.” What Walden had to teach him.

Thoreau says his Normal World is a “comparatively free country,” but normal people “are so occupied with the factitious cares” that they aren’t actually free. They have plenty of negative freedom: freedom to “get what they want.” But they don’t have much positive freedom, because “what they want” (and the rat-race struggle to get it) takes all their attention. So they never have time or energy to work on changing what they want, learning to want things that don’t require them to struggle. The person back in normal world is a “slave and prisoner of his own opinion of himself.” An opinion that doesn’t actually come from himself at all. It comes from the world around him, the shadows on the wall that tell him what’s good and bad, true and false, beautiful and ugly, worth wanting and not worth wanting.

If you’re a prisoner of your own opinion, you don’t even know you’re in prison. You think you freely chose your way of life. And you look around and assume that the whole thing, society itself, is like that: the result of free choices made by people who are aware of all the options. But this is false. Everyone is asleep; everyone takes everything for granted.

It’s never too late to give up our prejudices. Never too late to practice those philosophical movements of the mind that clear away the smoke. But it’s hard to do it when you’re surrounded by the people who are blowing the smoke. You clear a little of that smoke from your mind, you have a brief moment of clarity, but it passes, and you’re back into the daily grind, and the smoke builds up again. You don’t have a chance. Never too late to give up our prejudices; but at some point it’ll be too late to build that cabin in the woods where you can start the work of giving-up. Giving up distractions so you can pay attention. In normal world, there’s a constant supply of fresh smoke, reinforcing all the old opinions, burying all the assumptions deeper and deeper into the ground of your mind, distracting you from the big questions that might unearth them so you can examine them. You’ve got find some time to walk away.

Time to walk away, clear the smoke, and find what you’ve really been wanting this whole time, which is just reality. “Be it life or death, we crave only reality. If we are really dying, let us hear the rattle in our throats and feel cold in the extremities; if we are alive, let us go about our business.”

What you want now, in normal world: to not have a rattle in your throat, to not feel cold. That’s what the cave teaches you to want. That’s what you learn in school. Get pleasure, avoid pain. Get the carrot, avoid the stick. And of course death is the ultimate pain, the ultimate “bad thing.” It seems so obvious! So natural. But it’s not. That’s what Thoreau is saying. It’s a smokescreen. It’s an illusion that keeps you buying anti-aging cream. It’s not nature, it’s nurture. What’s really natural for you, for all human beings, is to want truth. Just truth. Even if it’s painful, like a cold shower in the morning. What you want, what you really need, what’s really worth wanting, is what the cave hides from you, what the cave makes you not want.

This is why you’ve got to get out of the cave. You’ve got to have something to compare to the “truth” of the cave, the stuff that seems so obvious. Get out, get some perspective, and you’ll see that it’s not obvious at all. And then maybe you can learn how to want what’s good for you. You can learn that even pain is good for you.

“The greater part of what my neighbors call good I believe in my soul to be bad.” What do his neighbors call good? Getting the grade, getting the job, getting the money, getting the reward. That’s what his neighbors call happiness. Shepherd’s happiness. Getting what you want. Why does he call it all bad? Not just because what they want might be bad for them. It’s also because what they want is distracting them from learning how to want better things. Just like Weil: the desire for the good grade distracts you from what’s really worth desiring, which is knowledge itself, knowledge for its own sake. But Weil stays in school, learning how to block out those distractions even while she was surrounded by them. Thoreau drops out. Once you’re no longer surrounded by distractions, it’s easier to realize that that’s what they were: distractions. Then you can start the work of choosing.

But there’s the other angle to this, the political angle. Distractions give some people power over others people. “If some have the pleasure or riding on a rail, others have the misfortune to be ridden upon.” What the neighbors call good: being able to get from point A to point B faster. Easy to sell them a new railroad, then. Easy to distract them from the fact that them getting what they want means other people suffering. (Thoreau is thinking here about all the immigrants who died like flies while building those railroads.) Easy to distract them from the child in the basement.

There’s the “pleasure of riding on a rail,” the pleasure of the average joe; and then there’s the pleasure of the railroad baron, who’s getting rich selling this pleasure to the average joe, selling this pleasure that’s only a pleasure because it’s a distraction. There’s the pleasure of the prisoner, chasing the shadow of “convenience,” and there’s the pleasure of the puppetmaster, selling this shadow as reality. The real point, Thoreau’s real point, is that both of these pleasures are illusions. The greater part of what the neighbors call good, the philosopher calls bad. He calls them bad in the name of a higher good, in the name of real morality.

But what is “real morality”?

A very simple thing, thinks Thoreau. It is simplicity itself. The good life, the happy life, is the simple life. The simple life is good and happy because only by stripping away all the distractions — the endless wants, the wants we’re made to have — can we see the simple truth, which is simply this: life is good. Life is good. All of it.

To see this, to see that life is good, is to wake up. That’s doing philosophy: trying to wake up. This is how you change your life. “Moral reform is an effort to throw off sleep. . . . To be awake is to be alive. I have never yet met a man who was quite awake. How could I have looked him in the face?”

What are we missing, while we slumber, distracted by our nightmares and our daydreams? What happiness are we missing out on? What happiness might we wake up to if we could only rouse ourselves? That is the point of doing philosophy. The point is to wake up. To wake up to the fact that most of what gets called good by your neighbors is bad, and to the fact that they call those things good not because they have thought about them but because of advertising, rhetoric, propaganda, manipulation, common sense, dead tradition, schooling in every sense of the word. To wake up to the fact that this describes not just your neighbors but you. And me. All of us. “I have never yet met a man who was quite awake.” Maybe no one has ever really been awake. But we can try. We can do philosophy.

But this is the thing we have to say about doing philosophy, about waking up, and especially about staying awake, minute by minute, day after day. We have to say that it is hard: it is unimaginably hard. It is unimaginably hard, not to do logic, not to learn how to argue, not to practice the Basic Move or anything like that; rather it is unimaginably hard to keep doing it, and to do it in the right posture of mind. It is unimaginably hard to do philosophy as a way of life. Day in and day out.

Read the next, last chapter to find out just how hard it is, and what it can mean to fail.

Reflection

- What is your general reaction to Thoreau’s challenge? Is it inspiring? Frustrating? Does it give you any specific ideas about how you might change your life? Or does it seem impractical?

- “The greater part of what my neighbors call good I believe in my soul to be bad, and if I repent of anything, it is very likely to be my good behavior.” Can you give an example of something you’ve done only because everyone around you says it’s good (the right thing to do, the thing that will make you happy) even though you believe it’s bad (the wrong thing to do, the thing that will make you unhappy?

- How does Thoreau seem to define “freedom” and “happiness”?