6 Slander

The Sixth Chapter,

in which you ask yourself

How do I get out?

Preparation

Required Reading: Webber, “Sedimentation: The Existentialist Challenge to Stereotypes” (Aeon)

Optional Reading: Illich, “The Sad Loss of Gender” (NPQ)

Writing:

- Webber’s key term is “sedimentation.” How does he define it? How does it relate to the more common term “stereotype”? Answer with paraphrase, not quotation.

- An argument is a thesis supported by one or more reasons. What is Weber’s thesis? What reason(s) does he provide in support of his thesis? Paraphrase or quote briefly.

- What is your immediate reaction to Weber’s argument? Agreement, disagreement, or something else?

- Respond to the following question by writing at least one paragraph:The author says: “Because girls and boys are subject to different expectations, we develop gendered sets of goals and values.” Someone might object that girls and boys are born with different kinds of goals and values, and this is why they are subject to different expectations. What position would you take in that debate?

Introduction

“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” That is a famous line from a famous book from the 20th century called The Second Sex, by Simone de Beauvoir. You’re not reading it for this chapter, but it’s a great way to introduce what you are going to read, which is Christine Di Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies, which was written 500 years earlier.

“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” That is a famous line from a famous book from the 20th century called The Second Sex, by Simone de Beauvoir. You’re not reading it for this chapter, but it’s a great way to introduce what you are going to read, which is Christine Di Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies, which was written 500 years earlier.

“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” What does it mean?

It’s about nature versus nurture. That’s one of the oldest Big Questions there is, and one that’s humming in the background of most things you’re reading here. What part of you comes from “nature,” and what part of you comes from “nurture”? Beauvoir said femininity comes from nurture: it’s not “natural” that being a woman means being (for example) meek and demure, or interested in clothes, or not interested in politics, or whatever stereotype is operating in a particular time and place. That’s a “social construction.”

This is a pretty obvious idea to most people now. (And that’s partly because Beauvoir made it obvious.) But Beauvoir doesn’t leave it at that. In The Second Sex, she explains in detail how that process of social construction works. And the thing is, the process works the same way in every master-slave, superior-inferior relationship. She’s interested in the men-women relationship, but the same dynamic shows up in the white-black relationship, for example (which is the subject of the next chapter).

The dynamic is what we usually call a “vicious cycle” (as opposed to a virtuous circle). Think back to the time when women basically weren’t allowed to be doctors or scholars or lawyers (or philosophers). How did men justify that? Well, it was that they weren’t cut out for that kind of work: their “nature” wasn’t suited to it. And what kind of evidence did men have for that? Plenty! Most women, after all, weren’t capable of that kind of intellectual work. But you should be able to see the flaw in this reasoning. If women weren’t capable of intellectual work, it probably had something to do with the fact that women weren’t allowed to do intellectual work. They didn’t go off to college, they weren’t encouraged or given the time and space to study, and so on. And who prohibited them? Men!

So that’s the vicious cycle. It works like this: one group of people has an idea about the “nature” of another group of people. The first group “nurtures” the second group until they (the second group) becomes what the first group says they already are. And then the first group points to what they’ve become and takes it as proof that their idea was right. The first group puts the second group in a box; then the people in the second group “become” the box they’re in. And then the first group looks and sees only the box, and conclude that they were right. You make people into what you think they are. They become that. And then you use what they’ve become to prove that they are who you think they are.

In the following selected passages from Book of the City of Ladies, Christine di Pizan is going to talk about “slander.” Use that word to sum up Beauvoir’s idea of the vicious circle. Men “slander” women; but many women believe the slander — they accept men’s “nightmares” about women as realities, and they get trapped in those nightmares. So they’ve got a lot in common.

But there’s also an interesting disagreement. Beauvoir says ideas about women’s “nature” are an illusion: nature is just nurture in disguise. The goal of doing philosophy is to rip off the disguise so you can take responsibility for freely choosing what you’re going to “become,” instead of blaming who you are on “nature” or on nurture. That’s what she’s interested in: freedom, the freedom to choose, which is also the responsibility to choose. Interestingly, she doesn’t think this “freedom” necessarily leads to “happiness.” She says: “I am interested in the fortunes of the individual as defined not in terms of happiness but . . . of liberty.”

But Pizan says that there is such a thing as a “female nature” — not just biological sex, but a natural way to be a woman. Women’s nature isn’t what men say it is; but there is such a thing as a “women’s nature” (and a men’s nature, and a “human nature,” a right and wrong way to be human). And the goal of doing philosophy isn’t just to rip off the disguise, so you can see that it’s all nurture, all the way down, nurture that you can resist by making a choice. The goal is to rip off the disguise so you can see true nature, so you can see that it’s not up to you to “choose” how to be a woman, or a man, or a human: you don’t have that kind of freedom. Rather it’s up to you to follow the right path. And if you do, you will be “happy.”

Freedom versus happiness. Is there a tension between the two? Can you not have both? (And what does each word mean?)

Keep this in mind as you go forward.

Selections from Christine di Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies

In the beginning of her book The City of Ladies, philosopher and theologian Catherine De Pizan describes her experience of reading works of philosophy and poetry as written by men and the negative attitude they have toward women, and wonders,

“..why on earth it was that so many men, both clerks and others, have said and continue to say and write such awful, damning things about women and their ways.”

While she cannot find any proof from her own personal experience to verify the claims of these writings by men regarding women, she decides,

“…I had to accept their unfavorable opinion of women since it was unlikely that so many learned men, who seemed to be endowed with such great intelligence and insight into all things, could possibly have lied on so many different occasions… Thus I preferred to give more weight to what others said than to trust my own judgment and experience… I came to the conclusion that God had surely created a vile thing when He created woman.”

This conclusion sends her into a fit of despair and makes her despise the whole of her own sex. As a devout Catholic, she begins to question why God, Who only creates good things, could create a being deemed so vile as woman is. She even beings to regret her own birth, lamenting,

“Oh God, why wasn’t I born a male so that my every desire would be to serve you, to do right in all things, and to be as perfect a creature as man claims to be?”

As this fit of despair is making her sick at heart, Catherine receives a vision of “a beam of light, like the rays of the sun…” From the beam of light appear the figures of three crowned, majestic ladies. The vision of these women at first frightens Catherine, fearing it to be an apparition come to tempt her. However, one of the ladies reassures her, saying,

“Our aim is to help you get rid of those misconceptions which have clouded your mind and made you reject what you know and believe in fact to to be the truth just because so many other people have come out with the opposite opinion… Don’t you know that it’s the very finest things which are the subject of the most intense discussion?”

The three majestic ladies are revealed to be Lady Reason, Lady Justice, and Lady Rectitude. Lady Reason reassures Catherine that the philosophers whom she is reading are not absolute authorities. In fact, they are all constantly questioning and correcting each other’s claims. Even the greatest of philosophers, Aristotle, has been challenged and disproven by subsequent thinkers and writers. Just because a philosopher has written something does not make it true. Thus, Catherine’s fallacious deference to their supposed (and often mistaken) authority has made her go astray and it is this that is troubling her mind, heart, and soul. The lady says to her,

“My dear friend, I have to say that it is your naivety which has led you to take what they come out with as the truth. Return to your senses… Let me tell you that those who speak ill of women do more harm to themselves than they do to the women they actually slander.”

The majestic lady reveals that they three are daughters of God,

“sent down to earth in order to restore order and justice to those institutions which we ourselves have set up at God’s command… Because you have long desired to acquire true knowledge by dedicating yourself to your studies, which have cut you off from the rest of the world, we are now here to comfort you in your said and dejected state. It is your own efforts that have won you this reward.”

By correcting Catherine, they also wish to prevent others from falling in to error as well. They note, “The female sex has been left defenseless for a long time now,” as there has been no one to defend them or testify against the erroneous charges of male writers against the female sex. The majestic lady then reveals that they three have been sent to charge Christina with the task, with their help, of constructing a walled city, a City of Ladies, which will be a home and protection for ladies “of good reputation and worthy of praise.” This city “will never fall or be taken. Rather, it will prosper always, in spite of its enemies who are racked by envy. Though it may be attacked on many sides, it will never be lost or defeated.” The completion of this task will serve as a corrective to the misjudgments and misapprehensions of the fallible mind of men, and as a building up the correct estimation of women according to divine reason and divine justice.

The revelation of the three divine ladies, and the setting out of their task both dispels the dismay from Catherine’s heart, but also causes her in her humility to question whether she is strong and learned enough to complete such a behemoth task. However, trusting to God’s judgment, she accepts the work and the help and command of the ladies. As she beings her work, she notes that she already feels stronger and lighter than before due to the presence of the three ladies.

While working, Christine questions Lady Reason, asking whether it is hatred or nature that makes men slander women. Lady Reason responds, “… far from making them slander women, Nature does the complete opposite. There is not stronger or closer bond in the world that that which Nature, in accordance with God’s wishes, creates between man and woman.”

She continues, “Some of those who criticized women did so with good intentions: they wanted to rescue men who had already fallen into the clutches of depraved and correput women or to prevent others from suffering the same fate, and to encourage men generally to avoid leading a lustful and sinful existence.”

In seeking to do this, they ignorantly and stupidly attacked all women. However, Lady Reason notes, “… there is no excuse for plain ignorance. If I killed you with good intentions and out of stupidity, would I be in the right? Those who have acted in this way, whoever they may be, have abused their power. Attacking one party in the belief that you are benefiting a third party is unfair. So is criticizing all women…” She explains that criticizing all women for the bad actions of a few particular cases is like criticizing fire in general, which is good and beneficial for mankind, for a few particular cases of fire causing injury and destruction; or it is like criticizing water, which is essential for mankind, because of particular cases of people drowning in it. Things in themselves should not be blamed because they can be put to bad use in particular cases. She says, “I can assure you that those writers who condemn the entire female sex for being sinful, when in fact there are so many women who are extremely virtuous, are not acting with my approval. They’ve committed a grave error, as do all those who subscribe to their views.”

Lady Reason continues to offer other reasons for the critical writings of men on women, saying, “Other men have criticized women for different reasons: some because they are themselves steeped in sin, some because of a bodily impediment, some out of sheer envy, and some quite simply because they naturally take delight in slandering others. There are also some who do so because they like to flaunt their erudition: they have come across those views in books and so like to quote the authors whom they have read.” Thus, Lady Reason posits that the attacks male writers have made on women are caused not by the deficiencies of women, but by the deficiencies, failings, and vices of the men themselves.

The men who attack women in such a way not only do harm to women, but to themselves in not recognizing and having gratitude for “the good and indispensible things that woman has done for him both in the past, and still today, much more than he can ever repay her for. Against nature, in that even the birds and the beasts naturally love their mate, the female of the species. So man acts in a most unnatural way when he, a rational being, fails to love woman.”

At this point, Christine starts asking about specific writers and books, especially poets, which have railed against women, and the motivations the men had for writing them. Lady Reason posits that many of these writers wrote disparaging things due to their own lustful desires, or from a bare hatred that they hoped to spread to other men. Of one Latin book in particular, On the Secrets of Women, Lady Reason states, “You shouldn’t need any other evidence than that of your own body to realize that this book is a complete fabrication and stuffed with lies… Any woman who reads it can see that, since certain things it says are the complete opposite of her own experience, she can safely assume that the rest of the book is equally unreliable.”

Christine next questions the notion popular among some philosophers that woman are the result of some sort of deficiency or weakness in the natural processes of gestation in the womb, and thus are a lesser sort of being as compared to men. Appealing to a theological viewpoint, Lady Reason says, “How can nature, who is God’s handmaiden, be more powerful than her own master from whom she derives her authority in the first place? It is God almighty who, at the very core of His being, nurtured the idea of creating man and woman.” Expanding on the creation story in the Book of Genesis, when Eve is made from the rib of Adam, Lady Reason explains, “This was a sign that she was meant to be his companion standing at his side, whom he would love as if they were one flesh, and not his servant lying at his feet. If the Divine Craftsman Himself wasn’t ashamed to create the female form, why should Nature be? It really is the height of stupidity to claim otherwise. Moreover, how was she created? I’m not sure if you realize this, but it was in God’s image. How can anybody dare to speak ill of something which bears such a noble imprint?”

Lady Reason goes on to explain it was not just man who was made in God’s image with an immaterial soul and intellect, but man and woman. Sex does not decide the nobility or value of a human being, but, “It is he or she who is the more virtuous who is the superior being: human superiority or inferiority is not determined by sexual difference but by the degree to which one has perfected one’s nature and morals.”

Lady Reason next sets out to dispel some of the many myths written about women, such as their being beautiful but cruel; gluttonous and overindulgent; or vain and obsessed with their appearance. She points out that, contrary to what they claim in their writings, it is actually men who are prone to display gluttony and overindulgence, often frequenting restaurants and taverns to eat and drink to excess. She says, “It is extremely rare to find women in these places: not from shame, as some might suggest, but rather, in my opinion, because they are naturally disposed to avoid them altogether. Even if women were given over to gluttony and yet managed to restrain their appetites out of a sense of shame, they should be praised for showing such virtue and strength of character.” Lady Reason then goes on to say that while men are more likely to frequent restaurants and taverns, women are more likely to be seen in church, expressing their piety and doing good works of charity. Women, according to Lady Reason, are “…inherently sober creatures and… those who aren’t go against their own nature.”

Christine then brings up one more accusation often charged against women by men: that they are “weak-minded and childish, which explains why they get on so well with children and why children like being with them.” Lady Reason takes special affront to this, rebuking those who make such claims by saying, “It’s truly wicked of people to try to turn something which is good and praiseworthy in a woman – her tenderness- into something bad and blameworthy. Women love children because they’re acting not out of ignorance but rather a natural instinct to be gentle” Lady Reason goes further, reminding Christine that Jesus told His followers to become like children, turning this accusation made by men on its head and revealing it as a heavenly virtue. She then goes on to list numerous examples in the given in the Bible of women encountering Christ and, through their virtue and righteousness, gaining His blessing.

In answer to Christine’s question about why women are not allowed to present a case, bear witness, or pass sentence in a court of law, Lady Reason explains this by appealing to the different natures of men and women, which will be contained in the following lengthy quotation: “… you might as well ask why God didn’t command men to perform women’s tasks and women those of men. In answer, one could say that just as a wise and prudent lord organizes his household into different domains and operates a strict division of labour amongst his workforce, so God created man and woman to serve Him in different ways and to help and comfort one another, according to similar division of labour. To this end, He endowed each sex with the qualities and attributes which they need to perform the tasks for which they are cut out, even though sometimes humankind fails to respect these distinctions. God gave men strong, powerful bodies to stride about and to speak boldly, which explains why it is men who learn the law and maintain the rule of justice. In those instances where someone refuses to uphold the law which has been established by right, men must enforce it through the use of arms and physical strength, which women clearly could not do. Even though God has often endowed many women with great intelligence, it would not be right for them to abandon their customary modesty to go about bringing cases before a court, as there are already enough men to do so. Why send three men to carry a burden which two can manage quite comfortably?” Thus, according to Lady Reason, particular differences and inequalities in men and women are explained by their different natures and the different ways and reasons they were made by God. However, in what they share, such as the ability to seek virtue, truth, and justice, they are equals and partners.

Christine wonders why, if women are as capable as men in the sphere of the intellect, men claim that they are “slow-witted.” Lady Reason replies, “I repeat – and don’t doubt my word – that if it were the custom to send little girls to school and to teach them all sorts of different subjects there, as one does with little boys, they would grasp and learn the difficulties of all the arts and sciences just as easily as the boys do… although women may have weaker and less agile bodies than men, which prevents them from doing certain tasks, their minds are in fact sharper and more receptive when to do apply themselves. The reason woman know less than men, according to Lady Reason, is that, “…they are less exposed to a wide variety of experiences since they have to stay at home all day to look after the household. There’s nothing like a whole range of different experiences and activities for expanding the mind of any rational creature.” Lady Reason strengthens her argument by saying that in places where men themselves do not receive a thorough and modern education, they “…are so backward that they seem no better than beasts… All this comes down to their lack of education…”

Christine wonders whether the lack of education in women has a negative effect on their moral judgment, as “…knowledge of the sciences should help inculcate moral values.” Lady Reason assures her that just as women have equal capabilities to men in scientific knowledge, so do they have an inherent capacity for moral judgment like men. However, Lady Reason is quick to point out that, “…good judgment does not come from learning, though learning can help perfect it in those who are naturally that way inclined…” She points out that though countless women have not received the high level of education that men have received, nonetheless they, “…prove themselves to be extremely attentive, diligent and meticulous in running a household and seeing to everything as best they can.” Women go about this diligent work while often having negligent, lazy husbands at home, thus exhibiting their dedication and moral virtue.

Christine wonders, then, if it true as these three ladies, Reason, Rectitude, and Justice say, that women throughout history have been as capable, virtuous, and intelligent as men, why has one of them not written against the false and fallacious charges laid against them by male poets, writers, and philosophers, or why none of them has begun the building of the City of Ladies. Lady Rectitude informs her that this is according to God’s design for the eternal scheme of things. “This task of constructing the city was reserved for you, not them. These women’s works alone were enough to make people of sound judgement and keen intelligence appreciate the female sex fully without their having to write anything else.”

Christine de Pizan ends her book by founding her new city, addressing her female readers and telling them their mission from her thusly: “It will not only shelter you all, or rather those of you who have proved yourselves to be worthy, but will also defend and protect you against your attackers and assailants, provided you look after it well. For you can see that it is made of virtuous material which shines so brightly that you can gaze at your reflection in it… My beloved ladies, I beg you not to abuse this new legacy like those arrogant fools who swell up with pride when they see themselves prosper and their wealth increase… all you women, whether of high, middle, or low social rank, be especially alert and on your guard against those who seek to attack your honor and your virtue. My ladies, see how these men assail you on all sides and accuse you of every vice imaginable. Prove them all wrong by showing how principled you are and refute the criticism they make of you by behaving morally… may it please you to pursue virtue and shun vice, thus increasing in number the inhabitants of our city. Let your hearts rejoice in doing good.”

Discussion

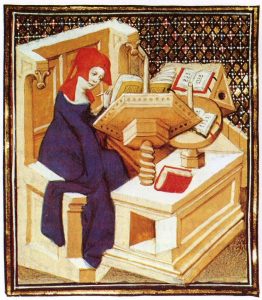

Where is Christine di Pizan at the beginning? She’s in her study, reading books written by men about women, and the men are saying women are less-than, they’re evil, they’re stupid, they’re temptresses, they’re bad. It’s a nightmare. She reads and she reads and she reads, and it’s like she’s been immobilized, forced to stare at the these shadows on the wall. She can’t look away, and those shadows, those images of who she is as a woman, they have their effect. She’s in “a deep trance” — hypnotized by “common sense,” by “expertise.” She believes the slander. She sees herself through their eyes. She becomes what she sees.

So she’s in a cave. It’s the cave where men are the masters and women are the slaves, the cave that that master-slave dialectic has been building up for centuries. It’s her normal world.

Stop and think for a minute about how that normal world appears to the men, the masters. Plato, when he’s talking about the cave, he’s talking to a specific group of people. If you read more from The Republic, you’d get to know them: they’re all men, for one thing. And not only that: they’re all rich, powerful men. So Plato tells them they’re in a cave, chained up, staring at shadows that tell them who they are and what’s worth wanting, what’s right and wrong, just and unjust, and you have to realize: they’re seeing different shadows. They’re shadows aren’t nightmares, like Pizan’s. They’re daydreams. The men get the daydreams (“this is the way things are, and it’s the way things ought to be: I deserve to be the master, she deserves to be the slave”). The women get the nightmares.

So Plato is doing philosophy in order to dispel the comforting shadows, the daydreams. But Pizan is doing philosophy in order to dispel the discomfiting shadows, the nightmares. Both are aiming to get out of the cave, or to help others get out of the cave. But the way out is going to be a bit different, depending on what you have to leave behind. Men, the winners of Hegel’s master-slave dialectic, will have to learn to feel dissatisfied with their daydreams. Women, the losers, will have to learn how to resist their nightmare.

Notice how both routes require a guide. Plato gives us Socrates, the first philosopher. Pizan gives us “the three ladies.” And now notice something else: where does Pizan meet these three ladies? She meets them in a dream! She’s in a “trance,” and she’s got to wake up. But the thing that wakes her up from the nightmare of Normal World turns out to be another dream.

Can one dream wake you up from another? Well, it’s not such a stretch, actually. Plato tells us we’re all seduced by stories and images, the shadows on the wall: but what’s the cave? It’s another story, another image. This is part of the whole idea of philosophy. Philosophy is supposed to wake us up to reality. But we do philosophy with words, with stories and images, and those aren’t “real.” Maybe if you start believing otherwise, if you take the words and stories and images too seriously, you fall back into the cave, just when you thought you were getting out. Basically: you have to let philosophy do its real work, without confusing philosophy with reality.

What do Pizan’s guides do for her? They build her a dreamcity: a “city in speech.” Not an actual city, a physical place. A city of words. A book.

She was already living in a city of words. All those books, containing all those words, the words that men had said about women. The nightmare city, where men rule and women obey, because men are good and women are bad. So the guides, they have to counter the nightmare words with true words. Not with daydream words: that’s not the antidote. But still, they’re just words. It’s not a utopia. It’s not about an actual revolution (not yet, at least). It’s a mental revolution. The guides build her a city in speech where she can wake up.

(Where she can wake up, mind you. Not where she’s guaranteed to wake up. The guides are teachers; this is an education. And an education is not about “imparting the truth,” like it’s a piece of information. An education is about learning how to seek after the truth. It’s not like you get a magic ring and then you’re out of the cave. The road goes ever on and on, up from the door where it began. Your teacher can only show you the door; you have to go through it, and then you have to keep going. And there will be obstacles, even after you stop staring at the shadows and turn your head around.)

Anyway: she can wake up in this city in speech because there, the shadows are held at bay.  The city is what another great thinker, Virginia Woolf, called “a room of one’s own,” the kind of room that men usually had and women usually lacked. It’s a place — a place in your head, mainly, but getting to that place usually requires having some literal space in the world, like Pizan’s study — where you find some relief from the constant pressure of opinion, where you no longer have to see yourself only through others’ eyes. Where you have the time to slow down your thinking, to reflect instead of just reacting. A dojo where you can practice the Basic move. A room where you can do philosophy. A city where you can just . . . wander around.

The city is what another great thinker, Virginia Woolf, called “a room of one’s own,” the kind of room that men usually had and women usually lacked. It’s a place — a place in your head, mainly, but getting to that place usually requires having some literal space in the world, like Pizan’s study — where you find some relief from the constant pressure of opinion, where you no longer have to see yourself only through others’ eyes. Where you have the time to slow down your thinking, to reflect instead of just reacting. A dojo where you can practice the Basic move. A room where you can do philosophy. A city where you can just . . . wander around.

The guides build Pizan a city in speech so she can wake up, but also so she can go on to build others a city in speech — other women. After all, Pizan is writing all this down in a book, which she hopes people will read. Pizan’s own book is the city in speech. It’s an invitation to try and see yourself clearly for who you really are. An invitation to leave illusions and seek truth (to seek truth: not a more comforting illusion). This is why the second face of philosophy — philosophy as a collection of books, a canon, a conversation — is so important. A great book, a great “city in speech,” can be your defense against nightmares.

What’s the goal of building the city? The goal of the Three Ladies, and Pizan’s goal? It’s a political goal: to “restore justice.” Pizan is doing not only philosophy but political philosophy.

What does this mean? She says that to “restore justice” is to make Normal World conform to the “pattern laid up in heaven” — to make society look like it was always supposed to be, before it got distorted by centuries of the master-slave dialectic. It means doing justice to herself — being willing to recognize the truth about herself, whether she likes it or not. She must be “ineluctable and immovable, having neither friend nor enemy who can overcome my will either by pity or by cruelty.” She’s not going to let people flatter her into thinking she’s better than she is, just because she’s spent most of her life letting people (men) bully her into thinking she’s less than she is. She’s not going to trade one illusion for another. Justice means giving herself her due: knowing herself, truly. Knowing what it really means to be a woman.

The Three Ladies restore justice by holding up a “mirror.” The mirror is philosophy. It’s the city in speech philosophy builds as it asks questions, challenges assumptions, and dispels shadows. It’s the mirror that shows you who you really are. Common opinion, conventional morality, is also a mirror. But it’s a funhouse mirror that distorts you, by showing a daydream version of yourself, or a nightmare version. The mirror of philosophy dispels the distractions that keep us from focusing on the truth. Pizan talks about “listening to the words of the ladies, which had commanded my complete attention and had totally dispelled the dismay that I had been feeling.”

The Ladies offer this justice-restoring mirror as a reward for Pizan’s own search for truth. They tell her: “you have long desired to acquire true knowledge by dedicating yourself to your studies, which have cut you off from the rest of the world.” There is no truth, no justice, without the desire for it. You cannot get free unless you want to. Philosophy doesn’t offer truth, as if it’s something you can possess; philosophy cultivates your desire for truth. Or, philosophy is what you do when you desire truth — desire it enough to “look into and correct yourself.”

And the three ladies — but they are Pizan herself, since she dreamed them — build the city also to “testify.” Those who have been made into inferiors by the master-slave dialect must be given a voice. Remember: the master-slave dialectic makes the loser of the battle into a thing, a box. The master says “it is natural that you are the inferior, that you obey and the master rules.” Women are naturally inferior, men are naturally superior. The dialectic isn’t just the master asserting his will; it’s the master justifying the result by saying “it’s not me, those are just the rules.” Women can’t rule because they are naturally not as smart/strong/whatever. Pizan testifies on behalf women because the voices of those who are placed on the inferior side of supposedly “natural” distinctions must be allowed to speak about their experience. The problem is that when you are kept from speaking, for so long, you actually lose the ability to speak, to perceive what’s wrong. And this confirms the distinctions, like a self-fulfilling prophecy. You become what the others say you are. Women are denied an education, because they are “naturally” less intelligent. Well, what do you think happens? They become less intelligent, because they’ve not been educated! And then the men say, “see, we are right.” So when Pizan testifies — when she writes a very intelligent book, a book that shows how much she’s read (the phrase “city in speech” actually comes from Plato’s Republic, the same book that contains the cave story) — she proves the men wrong.

To “look into and correct yourself,” to do justice to yourself — to do philosophy — is to learn to stop comparing yourself to other people, whether the comparison is favorable (daydream) or unfavorable (nightmare). You stop playing that game (which is really just the game the prisoner’s play, back in the cave). Philosophy means freedom from the game of comparison. That’s what it’s like, outside the cave. You don’t get pleasure from looking better than other people, and you don’t get pain from looking worse than other people. You get pleasure from being good, whether or not you look good to others.

So this is a key thing here: you aim to learn to love what’s good, what’s true. Clearing away the shadows, seeing through the illusions, is necessary, but it’s not enough. You also have to see reality. Philosophy is both things. It “deconstructs” all the nonsense, the conventional morality that people mistake for real morality. A lot of people stop there: they think that’s all philosophy does. And once it deconstructs, there’s nothing left, no limits: just you and your desires, and however much power you have to pursue them (so then you’ll want a magic ring, to take you beyond good and evil). But Pizan doesn’t stop there. There are two parts to her city in speech. There’s the refutation of the “slander” against women. The deconstruction of all the myths, the debunking of all the lies. But then there’s the positive part, the constructive part. She offers role models; evidence of women’s “virtue.” Examples of women who are good, regardless of how they seem, either to themselves or to others.

Ah, but now, we come to it. Pizan refutes all the things men say about how women are naturally bad. But she very much believes that there is a natural way for women to be — that to be a woman, to be a good woman, is to find that “pattern laid up in heaven” for what it means to be a woman. And this gets tricky. After all, isn’t that what the men claimed to have found: the truth about the natural way for a woman to be? For example, she says it’s true that there is “nothing worse than a woman who is dissolute,” that to be dissolute is to be a “monster, a creature going against its own nature, which is to be timid, meek, and pure.” Timid, meek, and pure? This is “woman’s nature”? Pizan agrees with men that this is “woman’s nature.” She thinks that is the “pattern laid up in heaven,” the right way for a woman to be, the way a woman must be if she is going to be happy. She thinks that women who live outside the cave will be timid, meek, and pure.

Pizan is using philosophy to fight stereotypes, to open up the boxes that men have put women in. But to modern readers, Pizan is also using philosophy to create or endorse stereotypes! What does this show?

Maybe it just shows this: that “doing justice” is really hard, that it’s easy to make mistakes, that philosophy doesn’t guarantee truth, and that seeking truth means accepting the risk that we will make a mistake and do injustice while we’re trying to do justice.

And it illustrates the big theme. The prisoner, Pizan, is entranced by conventional morality, which she confuses with truth. The puppetmaster — the Man — makes up this morality: he’s back there telling the prisoner “the truth” about her nature — telling her, for example, that to be a woman is to be “a seductress.” The puppetmaster himself thinks there is no truth at all; he just pretends to believe it, in order to get the power to get what he wants. The philosopher helps the prisoner see through the puppetmaster’s lies. But then the philosopher — Pizan, in this case — tells the prisoner the real truth about her nature.

Why should the prisoner believe the one, and not the other? How does the prisoner know who’s right? Aren’t we right back to where we started? Is there any way to get out of the cave and discover the real truth?

I don’t know. You should just remember two things. First, this is all words. It’s a city in speech. It’s not reality. The question whether the words point you toward reality, or put you back into your “trance.” The words are not the truth; the words are tools for getting at the truth. Second, that’s not even right: the words aren’t so much tools for getting at truth. They’re tools for waking up your desire for truth. Pizan’s desire, rewarded and guided by the Three Ladies, leads her toward certain conclusions. Your desire might lead you toward other conclusions. She might be wrong, you might be wrong. The difference between the puppetmaster and the philosopher is not which one is right and which one is wrong. The difference is about which one accepts the possibility of being wrong. The difference is about which one is willing to “look into and correct herself.”

If there’s any way out of the master-slave dialectic, it’s got to involve this willingness — on the part of the slave and not just on the part of the master — to respect yourself enough to admit that you can be wrong, even when you’re trying to resist nightmares and work for justice.

In the next chapter you will read about someone else’s attempt to escape a cave where the shadows are nightmares. In Pizan’s cave, it’s men and women: gender is the line between master and slave. In W.E.B. Du Bois’ cave, it’s white people and black people: race is the line, and the terms “master” and “slave” are literal.

Reflection

- Give an example of others wrongly perceiving something negative about you, and treating you accordingly. (For example, people might think you are “standoffish,” and treat you accordingly; but really you are just shy.)

- Give an example of others wrongly perceiving something negative about you, and treating you accordingly — but you start to conform to their perception, and behave in the way they expect. (For example, people might think you are an “angry” person, and treat you as such, and this makes you angry, which confirms their perception.)

- Give an example of others rightly perceiving something negative about you, something you had not noticed or would rather not admit. (For example, you might be a bit lazy, and your teacher might see this, but “lazy” does not conform to your self-image, so you are surprised, confused, and maybe resentful when she suggests that your laziness is getting in your way.)

- Give an example of a stereotype often applied to your group which does not apply to you.

- Give an example of a stereotype often applied to your group which does apply to you.