8 Matrix

The Eighth Chapter,

in which you ask yourself again

“Where am I?”

Preparation

Required Reading: Francis, “Is This Life Real?” (Aeon)

Optional Reading: Horowitz, “Inside Your Dreamscape” (Aeon)

Writing:

- Francis describes “the simulation hypothesis.” What is it? Answer with paraphrase, not quotation.

- An argument is a thesis supported by one or more reasons. What is Francis’ thesis? What reason(s) does he provide in support of his thesis? Paraphrase or quote briefly.

- What is your immediate reaction to Francis’ argument? Agreement, disagreement, or something else?

- Respond to the following question by writing at least one paragraph: Does it matter whether or not we we can know whether or not live in a simulation? (Read that again carefully: the question is not whether it matters if we live in a simulation, but whether it matters if we can know if we live in one.)

Introduction

In the daylight, we will be able to distinguish what is our true “nature” from what is just the product of ‘nurture” disguised as nature. Then we will be free to be ourselves, instead of being imprisoned in the shadows of ourselves that others have made for ourselves. And we will be able to relate, not as inferiors and superiors, but as equals.

That’s the hope. But now things are going to get tricky again. Remember: there is always a Bigger Question. The Bigger Question here is: How can we really tell the difference between nature and nurture, reality and social construction, sunlight and firelight? How can we know if we’ve really left our cave, or just entered a different one?

Here is another way to ask this question (which, you might notice, is the second kind of big question, an epistemological question). When you talk about what’s “natural” for you, or what’s “natural” for all humans, you’re talking about a set of limits. A limit is something you can’t cross without suffering, without diminishing your happiness. Flying is natural for birds, but not for people. If people try to fly (on their own, without a machine), they’ll fall and hurt or kill themselves. People are happy when they know their natural limits, just like birds or anything else.

The thing is, when you talk about what’s the result of “nurture,” you’re also talking about “limits.” How you’re raised, how you’re educated — you’re raised to believe you can do this, but you can’t do that. That if you do that, you won’t be happy, so you should do this instead. Women used to be “nurtured” into thinking that if they read too many books, they’d hurt their brains. They were nurtured into believing that was a natural limit that they couldn’t cross without making themselves unhappy. But that was an illusion.

So, you can’t distinguish nature from nurture by saying one limits you and the other doesn’t. Both limit you. But one is a real limit, and the other is fake. Both can keep you from doing what you want. If you’re a human and you want to fly, nature will frustrate you, and you won’t feel happy. If you were a woman in the past and you wanted to read a lot, nurture would frustrate you, and you wouldn’t feel happy. So the feeling of being frustrated, being unfree, isn’t enough to tell you which is the real limit and which is the one other people want you to think is the real limit. It doesn’t give you the answer to this epistemological question.

When you read the cave story, you were supposed to think that everyone in the cave was limited in the bad way: chained up by illusions about what they could and couldn’t do. Chained up either by normal morality (the shepherd, the prisoners) or by the illusion that there is no morality, no limits at all (the shepherd-with-the-ring, the puppetmasters). And the prisoner outside the cave (the philosopher) is limited in the good way: freed from nurture by knowing the truth about nature. Freed from the desire to fly like a bird, which can only frustrate him; free to wander around, watching the birds fly without wanting to be what he’s not.

But here’s the thing. Inside the cave, the prisoners and the puppetmasters think they “know the truth about nature.” Outside the cave, the philosopher also thinks he “knows the truth about nature. And then he goes back into the cave and tries to tell them . . . the truth about nature. He tries to tell them what their limits are. Why shouldn’t they be suspicious? He’s telling them not to listen to people who tell them about their limits. Now he’s telling them about their limits, telling them they shouldn’t want this or that, that they should want other things. He’s telling them they’ve been misled by their education, by their nurture. Now he’s trying to nurture them!

Slander, double consciousness — power is always a case of making people believe that artificial things are natural things, that Normal World morality is Real morality, that the fire is the sun. Everyone always claims they know what’s “natural.” The philosopher claims that, too. And the philosopher is really good at making people believe things. Maybe the philosopher isn’t taking people outside the cave at all. Maybe the philosopher is just taking people into a different cave, one that he built to his own liking. Maybe the philosopher is just another puppetmaster, no different from the marketers and influencers and news anchors and politicians he’s telling you not to listen to.

So now we’ve unearthed the next assumption: that there’s any natural “outside” to the cave at all. In a way, this takes us back to the story of the shepherd and the ring. Maybe the shepherd was right, after all. Maybe normal morality is what’s fake, but also, our desires are what’s real. Maybe the “real morality” the philosopher offers is just his own opinion, disguised as “knowledge of the truth.” Maybe there are no limits to what we can want and be happy. Maybe all limits are just limits that other people place on us. Maybe we can be happy no matter what we want, so long as we are the ones who get to choose. Maybe choice is the only thing that matters.

Think about this “maybe” while you watch The Matrix. After you watch, come back and read the rest of the chapter.

Discussion

Anyone who’s read Plato’s Allegory of the Cave will see that The Matrix is a retelling of that story. (You can also see it as a retelling of Alice in Wonderland, or of the Christian gospel – there is more than one way to interpret it.) The parallels are obvious. The matrix is the cave itself; the machines and the agents are the puppeteers; the humans are the prisoners; Neo is the prisoner who gets free; and Morpheus is the one who drags him out and offers him what philosophy offers — “the truth: nothing more.” This list could go on for a very long time, but I don’t want to spend time on those kinds of details. Instead, I want to look at what’s new.

The Matrix brings into focus two ideas about “doing philosophy” that are not so clear in the story of the cave. If we look at these ideas, we can add some new layers to our picture of what we’re doing when we do philosophy, and what doing philosophy can do for us. These ideas won’t contradict Plato’s idea of philosophy; they’ll just help us understand it better. But The Matrix also seems to swerve away from the conclusion of the cave story: it has a different message, a different conclusion about what philosophy is for, about what you should do with your life. The cave story suggests that philosophy is for discovering the truth about human nature, and that this truth will liberate you from the illusions projected by your society. The Matrix suggests that whenever clever philosophers tell you they’ve discovered that sort of truth about what’s “natural,” that’s when you know that someone’s trying to pull the wool over your eyes. There is no “human nature.”

Red/Blue

The central scene of the movie is the scene where Morpheus offers Neo the choice between the red and blue pills. Neo chooses the red pill, and wakes up to reality. Like the Ring of Gyges, the red pill gives us an image of philosophy: it is not so much a piece of truth as it is a vivid experience that shows you the truth, and reveals that you have been deceived. The ring shows the shepherd the truth about Normal World, about normal morality, by giving him the power to escape consequences: it shows him that normal morality isn’t about good and bad at all, that no one actually cares about good and bad but only pretends to care (they pretend even to themselves), when all they actually care about is getting what they want. The red pill shows Neo the truth about Normal World, by literally interrupting the illusions that are being fed into his brain. It is because he no longer sees what the machines want him to see, that he is able to see reality. He stops seeing one thing, and starts seeing another. His attention is turned from this to that; he literally “turns around,” and sees where he has really been his whole life. Philosophy is supposed to give us this same experience of “waking up” by exposing us to Big Questions, and then to even Bigger Questions; by unearthing our hidden assumptions, and taking us further and further down the rabbit hole; by showing us over and over again that we don’t know what we think we know, that our ideas don’t add up: that we have been wrong.

In a later scene, Cypher tells Neo that since taking the red pill, his only thought has been: “why oh why didn’t I take the blue pill?” Cypher regrets his choice to let himself be awakened. Why? Because the red pill — like philosophy — offers “the truth: nothing more,” and the truth is pretty awful. The real world is cold, ugly, dirty, depressing, boring, full of fear and pain. They eat the same grey goop every day. Cypher knows the truth; but he is not happy. And so he decides to betray his friends, his fellow freed prisoners, to the agents, in order to be plugged back into the Matrix. “Ignorance is bliss.”

Truth is not worth it. It is better to be happy than to be free. And back in the Matrix he can be happy, because he’s arranged for his illusion to be the pleasant kind: the daydream kind. Illusions can be nightmares. But so can the truth. So the choice here isn’t between truth and illusion; it’s between nightmare truth, and daydream illusion. No wonder most people prefer the blue pill. No wonder most prisoners in the cave don’t want to be free. The world outside the cave is beautiful — birds flying around, stars shining in the sky, the bright sun smiling down on you. But Plato doesn’t actually think that the truth is necessarily pleasant; he just thinks that it is beautiful to know the truth, even if it is unpleasant. The matrix shows you the unpleasantness up front and center. You leave the daydream and what you find isn’t life in the sun; it’s life in “the desert of the real.” It’s a ruin. Full of horrors.

So The Matrix makes the stakes clearer than the cave story does. It’s not just that they prisoners will try to kill you if you go back and try to free them; it’s not just that people will be annoyed at you for asking big questions. It’s that some of the answers to those big questions are going to freak you out. They’re going to leave you feeling confused and alone. They’re going to shake the sense of certainty out of your life. They’re going to make you wonder whether anything really matters. They’re going to depress you. So it turns out philosophy is not just solving puzzles. No wonder that one great philosopher, Albert Camus, said that the only important Big Question was a very simple one: why shouldn’t I kill myself?

Now, if you are a sentient human living in 21st century America and spending any time on the Internet, you’ll know that “redpill” has become a common term for something that shows you, not just the truth, but the forbidden truth. It shows you a truth that you are not supposed to know. The idea is not just that most people don’t want the truth; it’s that most people don’t want it because they’re told that it’s a lie, that people who want them to consider it are trying to deceive them, that they’re being led down a rabbit hole, possibly even “radicalized” to believe things like . . . well, as soon as I give you examples, I’ll sound like I’m accepting some common or official assumptions about what’s true and what’s false. And the whole point I want to make is that the “redpill” experience is the experience of rejecting those common or official assumptions, of accepting the possibility that the common or official assumptions about the truth might themselves be lies, illusions that are used to keep you from discovering the truth.

Ok, I guess I will have to give you an example, just to make it clear. The common, official truth is that the Holocaust happened. Now, I’m betting that you don’t actually know that it happened: you weren’t there personally. You haven’t investigated it directly. You just know it because it was in your history book. You assume that it happened. The “redpill” might be some kind of Big Question that challenges this assumption. Being “redpilled” about the Holocaust would make you a “Holocaust denier.” It would make you someone who has been “deceived” — goaded into questioning something that shouldn’t be questioned, seduced by the promise of “the hard truth.” It would be unpleasant to learn that all your history books have lied to you, wouldn’t it? It would make you question other things you’ve been told. It would make you feel very uncertain. But the person who offers you the redpill says that if you go down this rabbit hole you are demonstrating your courage: you are showing that you care more about being free (free of lies) than about being happy (happy in the idea that you can trust what you are told about things this important). And of course, it would take some courage to explore that question. People would mock you and judge you. In some countries, denying the Holocaust is actually illegal. You can be punished for taking that particular redpill.

On the other hand, if the Holocaust did indeed happen, then it would be a terrible thing if a lot of people got tricked into believing otherwise. Your desire to be “courageous” and “open-minded” could lead you to accept a dangerous lie. Part of the reason for remembering the past is so that it does not get repeated. If we fail to remember the Holocaust, we might fail to prevent the next one.

Here is the point: in The Matrix, you as the viewer know that the red pill leads to the truth. But in the real world, you don’t know that. In the real world, you are taking a risk. You hope the red pill will dissolve the illusions and show you what’s real. But what if what you already know is what’s real, and the red pill is the thing that deceives you? What if your assumptions are right, and the questions are dangerous because they make you stop accepting them? What if the red pill is the source of the illusion? What if the redpill is what puts you in the matrix, instead of taking you out?

The “red pill” theme helps us to unearth an assumption that’s been buried in all of the previous chapters: the assumption that it is a good thing to be as open-minded as philosophy wants you to be. The assumption that’s good to challenge assumptions. And it’s not only philosophers who tell you to be open-minded. That is part of Normal World morality, too. You are constantly told to be “open” to things. But this turns out to be a tricker idea than it seems.

People are always tell you that they’ve pierced through the fake morality of normal world, the world of “nurture,” and discovered what’s “natural,” and that you need to be “open-minded” to the idea that you’ve been wrong about everything, or deceived about everything, and that this new idea they’ve found is the truth. But what if what they call “natural” is just what they want to “nurture” you into accepting?

You assume being open-minded leads out of illusions and into truth. Out of the cave, into the sun. But it’s possible that it it leads you out of truth and into illusions.

Thinking about the “red pill” in the context of what it’s come to mean, for us, in the Internet age — well, it really drives home the idea that philosophy is dangerous. And part of the danger is that there’s no way to know, before you do philosophy, what it is going to put in danger. It could endanger the illusions that make you happy; but it could also endanger the truth that makes you free. Doing philosophy is risky in a deeper way than you realized.

Kung Fu

When the freed prisoner returns to the cave, the others make fun him: since his eyes have gotten use the light, he’s no longer as good as they are at distinguishing one shadow from another. He stopped playing their games, because he saw that they were just games, that they didn’t matter. But because he stopped, he lost his skills. And so the prisoners conclude that his trip outside the cave, his experience doing philosophy, has been useless — has made him useless. They care about making money, looking cool, getting good grades, and “having fun.” Since he doesn’t care about these things any more, he’s no longer very good at making money, looking cool, getting good grades, or having fun.

But in The Matrix, returning to the cave is a different experience. Instead of being less skilled than the people who are still plugged in, the freed prisoners when they go back into the matrix are more skilled. They are faster, stronger, smarter: they can do things that the normal people can’t. They can do these things precisely because they know it’s all a game. Since they know it’s just a game, they are better at playing the game, and they can break the game’s rules. They other people think it’s real life, that it’s natural, and that therefore the limits are real. Neo and his friends know it’s not real life, that it’s fake, and that the limits are also fake. It’s like those rare occasions when people are dreaming and suddenly they become conscious that they are dreaming, without actually leaving the dream. And then they can choose what to dream. Just like Neo can choose to fly.

But they learn how to do these things while they are outside the game, outside the matrix, where they’ve got a room of their own. They have build a dojo, and they have to train. However, because they are outside the matrix, they can learn much faster than anyone inside the matrix could. Because they know it’s a game, they are better than normal people at learning how to play the game, and because they’re better at learning how to play, they’re better at playing. Because he no longer cares about competition, Plato’s freed prisoner no longer knows how to fight. But in The Matrix it’s the opposite: precisely because he no longer cares about competition — because he knows it’s all an illusion — Neo does know how to fight. He knows kung fu.

People in normal world have been making fun of philosophers for centuries. The stereotype is the absent-minded professor, who knows everything about everything that doesn’t matter, but forgets to put his pants on, or doesn’t know how to balance her budget. And there’s plenty of truth to that stereotype. But there’s also another way to think about what it means to do philosophy. What if, instead of making you useless in the normal world, caring about things that normal people don’t care about actually made you more useful in the normal world? What if doing philosophy made you better at doing other things, precisely because it made you take those other things less seriously? If you didn’t care about the competition for money and sex and status and grades, you’d be free of all the anxiety it provokes in normal people; and if you didn’t feel the anxiety, if you weren’t distracted by it worrying about winning, you actually be better able to concentrate on what it actually takes to win those games — if you were to choose to. But that’s just it: you’d also have the power to choose not to compete.

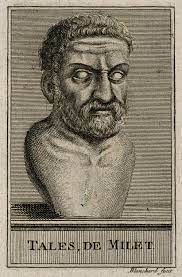

There’s a story that Aristotle tells about another philosopher, Thales of Miletus. The story goes like this:

Thales, so the story goes, because of his poverty was taunted with the uselessness of philosophy; but from his knowledge of astronomy he had observed while it was still winter that there was going to be a large crop of olives, so he raised a small sum of money and paid round deposits for the whole of the olive-presses in Miletus and Chios which he hired at a low rent as nobody was running him up; and when the season arrived, there was a sudden demand for a number of presses at the same time, and by letting them out on what terms he liked he realized a large sum of money, so proving that it is easy for philosophers to be rich if they choose, but this is not what they care about.

Thales, so the story goes, because of his poverty was taunted with the uselessness of philosophy; but from his knowledge of astronomy he had observed while it was still winter that there was going to be a large crop of olives, so he raised a small sum of money and paid round deposits for the whole of the olive-presses in Miletus and Chios which he hired at a low rent as nobody was running him up; and when the season arrived, there was a sudden demand for a number of presses at the same time, and by letting them out on what terms he liked he realized a large sum of money, so proving that it is easy for philosophers to be rich if they choose, but this is not what they care about.Thales lived outside the cave; but because he lived outside the cave, staring at the stars all day, he actually knew better how to make money than the people who lived inside the cave and never looked at the stars because they were too busy looking at their money. Philosophy is not really about what you know; it’s about what you care about. It’s not about what you can do; it’s about what you want to do, what you think is worth doing. But the twist is this: when you care about big philosophical things — when all you want is “truth: nothing more” — you might be able to do everyday things even better. When you know how to explore the Big Questions no one else cares about, you might actually be able to answer little questions everyone does care about more skillfully, and more quickly.

Another story connects this new idea back to the image of philosophy as a magic ring. This story comes The Lord of the Rings — which is, of course, all about a magic ring that makes you invisible and corrupts you with the promise of absolute power. No one can wear that magic ring, “the one ring to rule them all,” without getting corrupted. Those are the rules of the game.

Well, almost no one: there is one character who can handle the ring without getting seduced by the game in which the ring promises victory. This is the mysterious Tom Bombadil.

Show me the precious ring,” he said suddenly. . . . Then Tom put the Ring around the end of his little finger and held it up to the candlelight. For a moment the hobbits noticed nothing strange about this. Then they gasped. There was no sign of Tom disappearing! Tom laughed again, and then he spun the Ring in the air – and it vanished with a flash.

~J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

The ring makes anyone who puts it on invisible to others, but Tom can wear it without losing himself. And more than that: he can make the ring itself disappear. He can forget about the power it promises. And because he can forget about it, he can control it, instead of being controlled by it. The same ability makes it possible for him to see another person who is wearing the ring. Just as he is not tempted by the power to deceive others, he is not deceived by others who have given in to this temptation. He is immune to the game of power; and so he is more powerful than the people who play it. And he says: “Leave your game and sit down beside me! We must talk a while more . . . Tom must teach you the right road, and keep your feet from wandering.” (Oh but isn’t wandering good? Is there a “right road”).

Maybe we can think of philosophy in this way. It is a way of thinking and living that makes you immune to the game of the cave, the struggle for power among the prisoners, the false choice of mastery or slavery. This way is the “right road.” And yet, those who follow this right road are better equipped to play the games of the cave than anyone else, because they can bend and break the rules of those games. Philosophy is kung fu. You start with “wax on, wax off”: you start by practicing the Basic Moves, over and over again, not quite knowing what the point is. But you practice long enough, and suddenly you’re able to fly.

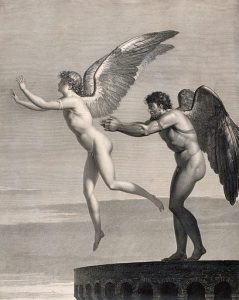

But let’s think more about that idea of flying.

Fly Away

What does Neo say at the end of the film? You’ve read these words already, back in an earlier chapter (if you pay attention, you’ll notice there are lots of words, phrases, whole sentences that get repeated throughout this book). He says:

I’m going to show them a world without you, a world without rules and controls, without borders or boundaries, a world where anything is possible. Where we go from there is a choice I leave to you.

After he says this, he literally flies off, like superman. For him, the matrix is now a “world without rules and controls.” But what he wants to show them — and us — is also a world without the matrix. That’s the goal of the resistance, after all: to destroy the matrix forever. So Neo is not talking here about what it is like for him to live it the Matrix, where the fake limits don’t apply. He’s talking about what it will be like for everyone once the matrix is destroyed: he’s saying the real world, the world without illusions, is a world without limits. Because all limits are illusions,

Is that true?

Plato does not show us “a world without rules and controls, a world without borders and boundaries, a world where anything is possible.” The prisoner who escapes the cave does not discover that all limits are illusions. He discovers that the limits he grew up with illusions: normal morality was an illusion. But once he’s outside, in the sunlight, there are still limits. He’s still a human being; he can’t fly like a bird. He can’t do whatever he wants and expect to be happy just because he chose to do it. In fact, that’s the illusion that he has gotten over: the illusion that deceives the shepherd, the delusion that keeps the puppetmasters inside the cave. Instead, he learns to want, to choose, what is truly good. He gets to decide what to do; but he doesn’t get to decide how that will affect him; he doesn’t get to decide what he ought to do. He learns not just to choose for himself; he learns how to choose the good for himself. There’s a right way to live, and a wrong way to live. There’s a way that leads to happiness, and there’s a way that leads to unhappiness. There’s good and evil, truth and falsehood, beauty and ugliness. Philosophy is not only for destroying illusory limits, the fake morality; it’s for revealing the true limits, the real morality. The moral limits that, if we submit to them, will make us happy. The freed prisoner does learn a kind of kung fu – the martial art that makes it possible for him to freely choose, day in and day out, to do what’s good. But it’s not the kind of kung fu that allows you to choose for yourself what counts as good.

So the story of the cave and the story of the matrix show you many of the same things about what it means to “do philosophy.” The Matrix also adds some ideas that don’t come through so clearly in the cave story, although they might be present there. But the two stories also lead toward very different conclusions about what philosophy can do, what it is for. In fact The Matrix almost seems to take us back to the story of the shepherd’s ring: it seems to say the shepherd was right, that the ring really did show him the whole truth. It almost seems to say: there is no “outside” to the cave. There is no “human nature.” We always live inside a cave, inside our own ideas. We get to choose what things mean, what is good and bad, right and wrong.

If you have seen the third film in The Matrix series, you will know that Zion, “the last human city,” where humans live outside the matrix, is located underground. The city is literally built inside a cave. It is “near the earth’s core, where it’s still warm” — and of course, what keeps it warm is not the sun: it is a fire, the molten rock at the center of the earth.

Plato tells the story of the shepherd and the ring in order to suggest that anyone who used the ring would use it for evil. The Matrix suggests that we could use the ring — use the power of philosophy to destroy the illusions that chain us down — without using it for evil. It suggests that the fear that power will lead us astray, the fear that there are limits to our ability to handle that power, is itself one of the fake limits that holds us back. Plato tries to make us afraid of using the ring. But that’s because he wants to keep the ring all to himself. And that’s how philosophers work. They offer to take you out of the cave so you can discover “the truth,” which they want you to think is “out there.” But of course it’s not out there: it’s just in their heads. They make it up, everything is made up. All limits are illusions, imposed on you by other people who want to control you. They tell you “this is just the way things are, I don’t make the rules.” But actually they do make the rules. So, you have to start making the rules for yourself. Just like they do.

The real truth, is that there is no truth, other than your truth, the truth in your head. The real truth is that there is no “outside” the cave; there’s just the realization that you have to make your own cave, make your own rules. That’s a lot of responsibility, and you have to train hard if you’re going to be able to to it. You have to learn kung fu. But it also means you can make your own cave, and that’s exciting. Don’t let philosophers tell you what’s natural. Become the philosopher. Decide what’s “natural.” Decide where you belong; decide who you are going to become.

“Where you go from here is a choice I leave to you.” Where we go from here is on to the next chapter, where you’ll read an essay that helps you explore this big question about what it means to choose for yourself — and whether there are any limits to what you can choose.

Reflection

- In Chapter Four, you identified the features of the situation in “the cave,” and considered how the cave situation is an analog for the general “human situation.” Do the same for The Matrix.

- Identify the significant features of the situation in which Neo finds himself. Be just as specific as you were when you identified the features of the cave.

- Compare the features of the cave to the features of the matrix. (For example, who are the “puppetmasters” in the matrix?) Are there any features of the matrix that do not exactly correspond to features of the cave? Are there any features that appear in one situation but not the other? (For example, is there something in the cave situation that corresponds to a “glitch in the matrix”?)

- The cave situation and the matrix situation are both analogues for the “human situation.” Are there any differences between what the cave story tells us about the human situation, and what the matrix story tells us?