2 Trolley

The Second Chapter,

In which you ask yourself:

What should I do?

Preparation

Required Reading: Owen, “Ethics on the Battlefield” (Aeon)

Optional Reading: Tadros, “It is sometimes right to fight in an unjust war” (Aeon)

Writing:

- Owen’s key term is “philosophy.” What does he mean by it? Answer with paraphrase, not quotation.

- An argument is a thesis supported by one or more reasons. What is Owen’s thesis? What reason(s) does he provide in support of his thesis? Paraphrase or quote briefly.

- What is your immediate reaction to Owen’s argument? Agreement, disagreement, or something else?

- Choose one of the philosophers or philosophical approaches mentioned here and explain it as much as you can, without doing any more research. Write at least 250 words.

The Basic Move

“What should I do with my life” is a very big question, and “change it” is a very big answer. Maybe it is too big. It might be better if you made the question smaller. Instead of thinking about your whole life, and how to change it, you might start by thinking about the situations that add up to your life. This kind of small ethical question is familiar. The question is: What should I do in this situation?

Here is a Normal World situation. It raises an ethical question. Someone answers it.

Adult: “What should you do when your friend wants to play with your toy?”

You as a kid: Take it away from her!

Adult: “No honey, you should share it with her!”

This is kindergarten stuff. Philosophy always starts with kindergarten stuff. Philosophy always starts in Normal World. But it doesn’t stay there. Remember:

1. There are no correct answers, only better and worse answers.

2. The best philosophers give different answers.

3. Philosophy means working hard to get it right, but staying relaxed about getting it wrong.

In the Friend-Wants-My-Toy Situation, the adult probably gave you a Correct Answer. She gave you a rule. But in philosophy, there are no rules, and you are not in kindergarten anymore. You have left Normal World. Your goal is not to learn the rules. It is to learn how to ask questions about the rules. Like:

What if the toy is a cup of peanuts, and my friend is allergic?

What if she’s got a history of asking me to share, but not sharing with me?

What if I love this toy, and it’s fragile, and she’s careless?

What if I don’t actually like her, and this is just a playdate mom set up without asking me?

When you ask questions like this, you make little changes to the situation. You add details, and the details add up. The details can flip the Correct Answer on its head. The Better Answer is the one you give after thinking hard about lots of details and how they matter. The Worse Answer is the one you give without thinking. The answer you give because someone else gave it to you.

Your head is probably full of Correct Answers that other people have put there, and you have not asked any questions about many of them. Your head is probably full of rules. Now, maybe you have broken the rules, and maybe you have rejected the answers. But that is not the same thing as asking good questions. Anyone can break rules and reject answers. Not everyone can ask good questions. But philosophers can. Or, that’s what you are working to do, when you are doing philosophy.

The Toy Situation shows you a basic philosopher’s move.

First, think about a situation that raises an ethical “what should you do?” question.

Then, answer this question with the first thought that pops into your head.

Now, think again about the situation. Change it a little in your mind. “What if it was like this?”

Watch how your first thought wavers. Now you have some second thoughts.

Repeat as many times as you can. Wax on, wax off.

We are going going to call this “the Basic Move.” It’s a simple “movement of the mind,” a philosophical “form,” like the forms or kata in martial arts. To make it easier to remember, we can boil it down to three steps:

1. See the situation

2. React to the situation

3. Reflect on your reaction

But all the action is in the third step: “reflect on your reaction.” So we need to break that down. You perform the reflection like this:

See, react, reflect. You are going to practice this Basic Move over and over. Wax on, wax off.

The Trolley Problem

Now you are going to read your first piece of philosophy. It is called “The Trolley Problem.” The philosopher who wrote about it was Philippa Foot, in 1967. She used the Trolley Problem to think hard about a very big ethical question, the question of abortion. Later another philosopher, Judith Thomson, used Philippa Foot’s Trolly Problem to think about other big questions. (This is a good example of that second face of philosophy: the books, the canon, the books some philosophers write about the books that other philosophers write. Philosophy is a conversation.)

Thomson wrote:

Some years ago, Philippa Foot drew attention to an extraordinarily interesting problem. Suppose you are the driver of a trolley. The trolley rounds the bend, and there come into view ahead five track workmen, who have been repairing the track. The track goes through a bit of a valley at that point, and the sides are steep, so you must stop the trolley if you are to avoid running the five men down. You step on the brakes, but alas they don’t work. Now you suddenly see a spur of track leading off to the right. You can turn the trolley into it, and thus save the five men on the straight track ahead. Unfortunately Mrs. Foot has arranged that there is one track workman on that spur of track. He can no more get off the track in time than the five can, so you will kill him if you turn the trolley onto him. Is it morally permissible for you to turn the trolley?

Some years ago, Philippa Foot drew attention to an extraordinarily interesting problem. Suppose you are the driver of a trolley. The trolley rounds the bend, and there come into view ahead five track workmen, who have been repairing the track. The track goes through a bit of a valley at that point, and the sides are steep, so you must stop the trolley if you are to avoid running the five men down. You step on the brakes, but alas they don’t work. Now you suddenly see a spur of track leading off to the right. You can turn the trolley into it, and thus save the five men on the straight track ahead. Unfortunately Mrs. Foot has arranged that there is one track workman on that spur of track. He can no more get off the track in time than the five can, so you will kill him if you turn the trolley onto him. Is it morally permissible for you to turn the trolley?

~ Judith Jarvis Thomson, “The Trolley Problem” in The Yale Law Journal 94, no. 6 (1985), p. 1395

The Trolley Problem is what philosophers call a thought experiment. A thought experiment is an imaginary situation that lets you play with ideas. In other words, it helps you think about your thoughts. It is a tool for doing philosophy (just like philosophy is a tool for changing your life). Even though the situation is imaginary, thinking about it helps you take a closer look at the thoughts you have about real situations. It helps you see what your thoughts are made of, where they come from, and how they fit together or clash with your other thoughts. The point of doing the experiment is not to “solve the Trolley Problem.” The point is to watch yourself thinking about that problem, so you can think about your thinking. And remember: the point of thinking about your thinking is that want to live a happy life, and your thoughts are part of that.

Maybe. Maybe not. We’ll come back to it.

The Trolley Problem helps you practice the Basic Move:

- See the situation. The situation is the trolley speeding down the track toward the five people. The question is whether you should divert the track and kill the one person, or do nothing and kill the five.

- React to the situation. What is your first thought? In this part, don’t think too much. Just react. Kill one or kill five?

- Reflect on your reaction. Why did you give that answer? What is your reason?

Of course, all the action, all the stuff we think of as doing philosophy, is in that third step, “reflection.” First, you change the situation a little in you mind by adding new features of the situation. “What if the one person was Hitler, and the five people were all Mother Theresa? Or, what if the one person was Mother Theresa, and the five people were all Hitler?” Next, you notice that you react differently to different versions of the situation. (“If the one person was Hitler I’d definitely save the five; but if the one person was my grandma, I’d have the opposite reaction.”) Finally, you try to explain why you react differently. (“Apparently I believe the number of people is not as important as the moral quality of the people.”)

By reflecting in this way, you learn to see how you think. And once you can see how you are thinking, you can think about whether you are thinking well, whether your thoughts are leading you in a good or a bad direction.

Again to make it easier to remember, we can break the third step of “reflection” down into three smaller steps:

Vary the situation. Add new features to the situation until your reaction to it changes. Ask “what if . . .?”

Observe your new reaction. Notice that your reaction has changed. Ask “what then . . .?”

Explain your new reaction.. Identify the feature of the situation that changed your reaction, and try to explain why it changed your reaction. Explaining it means answering this question: “what’s the difference?”

So, altogether, the Basic Move is a sequence that looks like this:

1. See the situation.

2. Reaction to the situation.

3. Reflect on your reaction by:

(3.1) varying the situation, (3.2) reacting to the variation, and (3.3) explaining your reaction by asking “what’s the difference?”

And now you probably notice that when you “reflect,” the basic move is sort of doubling back on itself. You see and then you react and then you reflect, but when you reflect, you see and then you react and then you reflect. And then that last “reflect” also contains seeing and reacting and reflecting, and so on and so on. Potentially forever (although you do have to stop to eat sometimes).

This is what philosophical thinking is like. It’s a spiral, like a double helix, folding in on itself for miles and miles, even though it’s just a little speck. Within every question, another question is folded up, and then another one, and then another one. The Basic Move is a way to unfold it all. It’s a way to unravel the spiral.

Features of the Situation

It’s worth pausing to emphasize this notion of the “features of the situation.” Now, it might seem obvious that every situation has various “features.” In The Trolley Situation there are lots of features: the two groups of people tied to the tracks, the lever that switches the trolley from one track to the other, the time you have to decide, the characteristics of the people. All sorts of things. Obvious. But – and this is a really important point – a lot of philosophy is actually about emphasizing the obvious. Because philosophers notice that a lot of times, when you take the time to spell out the obvious, you start to notice a lot of things that were not obvious. So while it’s true that a lot of the work of “doing philosophy” happens during the third step of the Basic Move, there’s also a lot of equally important but easily overlooked work that happens during the first step. In other words, a lot depends on what you see. And you can get better at seeing the situation, by trying to systematically identify as many features of the situation as you can.

It’s important to do this because your mind doesn’t automatically identify all the features. It doesn’t automatically notice everything. It only notices what it already thinks is relevant. And the whole point of doing philosophy, the whole purpose of the Basic Move, is to figure out whether what you already think of as important, really is important, and whether you are ignoring other things that might also be important.

When you encounter the situation, your mind notices some of its features and not others, and it divides the features it notices into “relevant” and “not relevant.” When you first encounter the Trolley Situation, the feature you immediately notice first is probably a feature you could label “Number.” As in, the number of people on the first track versus the number of people on the second track.

Number seems relevant to the question, “what should I do?” Five is more than one; so it seems right to some people — even if it does not feel good — to save five by killing one.

But other people say it’s not right. Why? Maybe because they notice another feature of the situation, besides Number. They notice that if you divert the train to kill the one and save five, you are doing something, whereas if you let the train go on without intervening, you are not doing something. You could label this feature of the situation “Passive/Active.” To these other people, the difference between actively killing someone and passively letting someone die seems very relevant. It seems more relevant than the number of people who will die.

What you have just done is to think about the thinking of people who give different answers to this question. In the same way, by practicing the Basic Move, you think about your own thinking. You ask: what does my first thought, my initial answer, tell me about what my mind has identified as the relevant features of the situation?

You are getting a glimpse of how your mind works. You are examining yourself.

Why does it matter?

When you were a kid, you probably found yourself in the Toy Situation many times. But you are probably not going to find yourself in the Trolley Situation. So, what is the point of thinking about the Trolley Situation?

Remember that the Trolley Situation is a “thought experiment,” which means the point is not to solve the trolley problem, but to use the trolley situation to think about how you solve real-world problems, like the toy problem. It helps you think about your thinking. So it helps you “examine yourself,” like Socrates said you should.

Ok. But the toy situation does not seem very important. It seems like an easy situation, and even if someone does not think very well in that situation — even if a person thoughtlessly follows the Share Your Toys rule, or thoughtlessly breaks it — does it really matter?

Well, yes it does. In philosophy, anything and everything matters, if you can see it right. If you learn in kindergarten to thoughtlessly follow the rules, or thoughtlessly break the rules, then you might grow up to be a thoughtless adult, and thoughtless adults can do pretty terrible things.

Go back to the Trolley Problem and change it again in your mind. What if:

The 1 was tall and the 5 were short, and you chose to kill the five, and your reason was that they were short? Would that be a good reason? Or would that be a bad answer to the question?

The 1 looked like you and the 5 were another ethnicity, and you chose to kill the 5, and your reason was that they were another ethnicity? Would that be a good reason? Or would that be a bad answer to the question?

If your first thought was to kill the short people, or the black/white/Asian/whatever people. . . well, you can see why it might make a moral difference whether people have bothered to “think about their thoughts.”

When you can see what your mind is doing when it answers a Big Question, you can go on to think about whether your mind is doing it right. And you can see why it would matter to be able to do this, when you see that people — and not just Those Bad People — often answer big questions on the basis of irrelevant features of the situation. When we do this, we get things like “racism.”

This is why your thinking matters.

Between the Stimulus and the Response

The Basic Move is a way to slow down your thinking. Maybe you imagined that philosophers are people who can think faster than normal people. That’s usually true. But if philosophers can think faster, it’s only because they’ve spent a lot of time thinking in a kind of slow motion.

Apparently, before motion pictures, no one knew that when horses run there’s actually a brief instant in which all four of their legs are off the ground, as if they’re flying. They ran too fast for the eye to see it. But on film, people could watch the horse run frame by frame, and they were able to see how it worked.

That’s what philosophers do. They slow down their thinking so they can see how it works. But when you know how something works, you can make it work better. That’s why philosophers can think “faster” than you can. It’s not so much that they think faster. It’s that they can think faster than their own thoughts. They have their second thoughts right along with their first thoughts; it’s like they can freeze their first thoughts in their second thoughts. The motion stops, and they can inspect it, and then they can decide whether to let their first thoughts keep going, or whether to change their first thoughts.

It’s like this: you’re going about your day, everything’s normal, and what that means is this: stuff happens, and you react. That’s normal world. The hammer hits your knee, your knee jerks. The question comes at you, you’ve got your Correct Answer ready to go. Normal world is knee-jerk world. There’s a social issue, and bam!, you’ve got your opinion. There’s a provocation, and bam!, you’ve got your emotion. Fear, anger, pleasure, pain, whatever. Stimulus-response.

But philosophy is like this: you’re going about your day, everything’s normal, stuff happens and you react, but then you STOP. You reflect on your reaction — you do the thing, you change the scenario in your mind, in order to understand why you reacted this way and not that way, whey you felt one way not another. The Basic Move.

Someone (not Victor Frankel) said:

By practicing the Basic Move, you open up the space between the stimulus and the response. You freeze the frame so you can examine what’s going on in that space. Because that’s just it: something is going on.

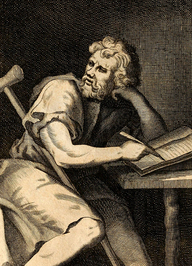

One philosopher, Epictetus, said this:

Epictetus is talking about the space between the stimulus and the response. In that space we are always making some kind of judgment. It’s not that something happens, and we feel happy. Something happens, and then we make a judgment that the thing is good, and then we feel happy. But we make it so fast that we don’t even notice it, and then we forget about it. We start to believe that we don’t actually make any judgment, and that means we start to believe that how we react to the stimulus is beyond our control, and that it’s not our responsibility. But Epictetus says we make a judgment. That means our judgment could be wrong; our judgment could be leading us to do the wrong thing. It could lead us to give a bad answer to the Trolley Problem. And it also means that we could make a different one.

Epictetus is talking about the space between the stimulus and the response. In that space we are always making some kind of judgment. It’s not that something happens, and we feel happy. Something happens, and then we make a judgment that the thing is good, and then we feel happy. But we make it so fast that we don’t even notice it, and then we forget about it. We start to believe that we don’t actually make any judgment, and that means we start to believe that how we react to the stimulus is beyond our control, and that it’s not our responsibility. But Epictetus says we make a judgment. That means our judgment could be wrong; our judgment could be leading us to do the wrong thing. It could lead us to give a bad answer to the Trolley Problem. And it also means that we could make a different one.

The Basic Move is all about slowing down your thinking so that you can see the judgment that made you react to the situation in the way that you did. The idea is that if you can see it, you can change it. And you can’t change it until you can see it.

But this is very hard to do. Unimaginably hard, maybe. So the question is: why bother?

All of this is supposed to be about “doing the right thing.” It matters how we think about the trolley problem because if we think about it in the wrong way, we may do the wrong thing. And it matters that we do the right thing because doing the right thing is connected to living a happy life.

But is it really? What if that is not true? What if doing the right thing and living a happy life are not connected, after all? What if being good and being happy are opposites? What if you could increase your happiness by being bad?

In the next chapter you will read another thought experiment, a story called “The Ring of Gyges.” This story wants you to ask the bigger question behind the big ethical question. If the ethical question is, “what is the right thing to do,” the bigger question is “why should I care about doing the right thing?” And the story suggests that the better answer may be: you shouldn’t.

Reflection

- Given an example of a situation where you had to (a) think about what would be the “right thing to do,” and (b) make a decision to do it, when you might have done something else, or not done anything at all.

- Think about that example, and then answer this question: in this particular situation, why did you care about “doing the right thing”? Be specific. “Examine yourself.”

- Give an example of a recurring situation (real life or online, factual or fictional, doesn’t matter) that provokes a certain reaction in you, but a very different reaction in someone else you know. (For example: something that scares you, but entertains someone else; something that makes you angry, but makes someone else laugh.) Can you identify the judgment you make about the situation that leads to your reaction? What different judgment might the other person be making that leads to their different reaction?